Sinning paid off…

Coffee was first introduced to Colombia around the same time Jesuit priests first began arriving from Europe in the mid-16th century. The leaders of Colombia tried to encouraged people to grow coffee, but they met with resistance. Worried that a coffee tree takes five years to provide its first crop, they wondered how they were going to survive during this period?

In a small village, a priest named Francisco Romero had an idea. Instead of the usual penance at confession, he told them to plant 3 or 4 coffee trees. The Archbishop of Colombia ordered everyone to use this penance thinking it was an excellent idea and it became the general practice. This started Colombia as the world’s second largest coffee producing country built on the penance of its forefathers.

You can’t visit Colombia without learning about coffee!

You can’t come to Colombia and not visit a coffee plantation. Many people visit those way up in the mountains, where they have to ride a horse for several hours to get there. We did not. We opted to visit one just outside of Jardin.

The area where the coffee is grown and where you find Jardin, is called Verdun. We drove for a short distance, out of the main town and through narrow roads with coffee fields all around us. We drove a little way up the mountain, and then we turned into a dirt driveway, leading to a beautiful, ranch-style home surrounded by a porch and had a large front yard filled with flowers and a bird house with all different small, colorful birds flying in and out. And in the distance the beautiful view of the mountains. This was the home of Martha and Gustavo Marin and the Margus (MARtha and GUStavo) coffee plantation. Gustavo inherited the land from his father, and is a fourth generation coffee farmer. Martha is also a fourth generation, having grown up in Jardin.

We were warmly welcomed by Martha and Gustavo and their daughter (and several cats). We were invited first to sit and learn about coffee, while of course, drinking the real thing. Gustavo taught us about the different beans and about the history of coffee in Colombia.

As we sat there enjoying one of the best cups of coffee we ever had, we watched the action on the road. I say that sarcastically, as it was so quiet here. A man on a horse rode by. A truck full of bags of coffee drove up the rode. And a chiva! Ah, but more on that below.

Colombian Coffee

Colombian coffee is grown at high altitudes. The coffee trees are often planted in the shade of banana and rubber trees. The volcanic soil in the arid mountains makes for ideal conditions for growing coffee. It often is described as a rich, full-bodied, and perfectly balanced taste. Colombian coffee is known to be among the best in the world, once second only to Brazil, but now third behind Vietnam.

Colombian coffees are grown in two main regions. The region of Medellin, Armenia and Manizales (MAM), in central Colombia, and where we were, are more heavy-bodied, rich in flavor with fine, balanced acidity. The area near Bogotá and Bucaramanga, which is more mountainous in the east, produce an even richer, heavier and less acidic coffee and are considered the finest of the two regions.

National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC)

Gustavo explained how they survive and why there is not more competition between the smaller coffee plantations. It all has to do with the National Federation of Coffee Growers, or the FNC.

The FNC is a non-profit business association, founded in 1927 to promote the production and exportation of Colombian coffee. It was founded with three objectives: 1) to protect the industry, 2) to study its problems, and 3) to further its interests. It represents about 600,000 farmers, most of whom have small, family run farms. The FNC is made up of smaller, local co-ops. While it is not mandatory to join the co-ops, 98% of farmers are members. The only requirement to join is that you must have 1000 coffee trees. These can be planted in an area as small as 100 sq. meters, so a farmer does not need a lot of land to grow coffee and be a member of the Federation. The National Federation gives money to the co-ops who then buy the coffee from the members.

There seem to be many advantages to belonging to the co-ops (and thus the FNC) as the FNC supports research and development, and monitors production to ensure high quality. Perhaps most importantly, however, it helps the farmers. Gustavo explained that coffee brought progress to the family and the area as the tax from the coffee is put back into the farms. That money was used for electricity, sewers, running water. Villages with no coffee farms have no electricity or sewers etc. Members get help from their local co-ops who send people to teach farmers how to best grow coffee and help them if they run into problems. Non-members are on their own. They also get discounts on pesticides etc. I was particularly impressed to learn that it is mandatory for the co-op to financially support education (including college) for the farmers’ children.

Coffee growing has also kept this area relatively safe. The guerrillas, a major problem in Colombia, mostly in the past (please see the post on Medellin), preferred going to villages with gold, not with coffee, so this also kept them safe.

The coffee is harvested in October through December but the co-ops have a lot of coffee in stock. It could take a year to sell it all. One has to be careful however, as after six months, the coffee begins to lose quality. The good news is that the growers get paid right away when they give the co-op the coffee, even if the co-op does not sell it right away. The price they get for their coffee depends solely on supply and demand (like everything). There is a minimum price however, and they never get paid below that price.

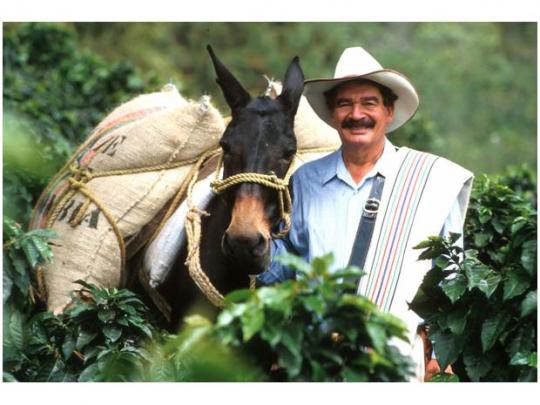

So what about Juan Valdez?

As I wrote in the blog about Cartagena, we all remember the Juan Valdez magazine ads and TV commercials. A good-looking coffee farmer, Juan, would pick the beans  off the bushes and his mule, Conchita, would carry the sacks of coffee, and that coffee would make its way to us. So who was Juan Valdez? And was there really a Juan Valdez? Sorry, no. He was a fictional character, sort of. The FNC developed the marketing program in 1981 to distinguish Colombian coffee from other coffees. Juan Valdez was the name of the family who grew the most coffee, so their name was used to promote coffee in general. But it was just a name with no face. So the Colombian government advertised for a model, that is, for a face to represent the coffee. They found the perfect face, but it was on a Cuban man. The Colombians complained. “A Colombian should represent our coffee.” So they advertised again and found a Colombian. And he became the famous face of Juan Valdez.

off the bushes and his mule, Conchita, would carry the sacks of coffee, and that coffee would make its way to us. So who was Juan Valdez? And was there really a Juan Valdez? Sorry, no. He was a fictional character, sort of. The FNC developed the marketing program in 1981 to distinguish Colombian coffee from other coffees. Juan Valdez was the name of the family who grew the most coffee, so their name was used to promote coffee in general. But it was just a name with no face. So the Colombian government advertised for a model, that is, for a face to represent the coffee. They found the perfect face, but it was on a Cuban man. The Colombians complained. “A Colombian should represent our coffee.” So they advertised again and found a Colombian. And he became the famous face of Juan Valdez.

Coffee beans

So what did we learn about the different coffee beans? The beans are picked when they are red. The skin gets removed, and is called green coffee at that point. It is pre-roasted and that is what is sold to the co-op and gets exported. The amount of roasting determines the flavor of the coffee. The roasting is done by the co-op.

I asked Gustavo if he feels he is competing with Juan Valdez coffee or Starbucks. He said no. Their coffee is a better quality and is mostly grown for export. They are allowed to export 100 pounds per month.

Picking coffee beans

After our lesson, and enjoying our coffee, it was time to pick some coffee beans. We all donned big hats, which we picked from their collection, to protect us from the sun and headed up the mountain.

Gustavo and Martha have 2,000 trees on this farm, but 30,000 coffee trees at another higher altitude location. Coffee grown at higher altitudes is the best at least at 1400-2000 meters above sea level. He has a family who lives on his land for free in exchange for taking care of the farm. They also share in his profits. Very equitable. I was shocked that number – 30,000! But he told me that is not considered a lot of trees.

Gustavo told us that they pick beans every day. If you collect the beans every day, you don’t have to use pesticides. (As an aside, artificial flavor is added to hide the taste of the pesticides). Out of every six kilos picked, they might end up with 1 kilo of coffee.

We walked among the avocado trees, plantain trees and yucca. The plantains are harvested every 15 days because they have so many of them. The fruit, that is, the plantains, are covered in blue bags to keep the birds and bugs away, and to make them easily ready for packing.

So, back to picking beans. Gustavo tied a coco around my waist. Coco is the bucket used to collect the beans. I walked along the rows of trees looking for the red beans, called cherries. It was not hard to find them among all the green ones. And what a lovely sound they made when dropped into the coco. Since we were just doing this for fun, we didn’t pick many, but just enough to get a feel for how hard the work is. Since all the beans are picked by hand, it is very labor intensive. A good picker averages approximately 100 to 200 pounds of coffee cherries a day, which will produce 20 to 40 pounds of coffee beans. I picked around 20 cherries.

So then what happens to the beans?

Next it was time to see what happened to the beans. Gustavo uses the wet method of processing which removes the pulp from the coffee cherry after harvesting so the bean is dried with only the parchment skin left on.

We walked back down the mountain to a house across the road from Gustavo and Martha’s house. The neighbors share in the coffee production. We walked across the lawn, past a small shrine and through the colorful laundry drying in the hot sun. The older gentlemen was sleeping on the porch, so we kept our voices low.

There, in a separate building was a machine, which Gustavo called the Benefit. The freshly harvested cherries are passed through this pulping machine which separates the skin and pulp from the bean.

After seeing a demonstration, we walked outside where the beans are separated by weight as they pass through water channels. The lighter beans, which are the bad coffee, float to the top, while the heavier ripe beans sink to the bottom. There is a dam which allows the lighter beans to pass over while the good beans are held back. Thus the good are separated from the bad.

The beans, still in their parchment envelope, now need to be dried. Gustavo and his men move them up to the roof where they are spread on the floor and the sun and humidity do their job. The roof has a cover in case it rains or the sun is too hot. There are special rakes to spread them and turn them. I got to climb up to the roof and rake the beans. Such fun. At least fun when you only have to do it for a few minutes.

Coffee and corn

We went back to the house where Martha had prepared fresh corn on the cob, just harvested the day before, and fresh arapas. And of course, more coffee.

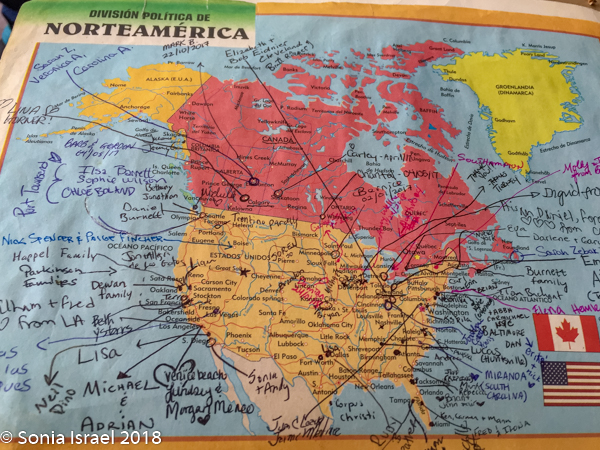

She toured us around her house. They had a map with marks for all their visitors and we added ours.

We enjoyed the food, the company and watching all the different birds darting in and out of the bird feeder. There was one in particular, the yellow turpial, of the oriole family, which seemed to be everywhere. The turpial is the national bird of Venezuela but doesn’t understand borders so is found here too.

Chivas

When we first had arrived at their house, we saw a Chiva go by. Chivas are the brightly colorful, rustic buses of Colombia. They are found in most of the smaller Colombian towns and are the most important means of transportation.

The word “chiva” comes from the Spanish for goat or “escalera’ for ladder or stairs. Escalera is self-explantory. There is a ladder in the back leading to the roof for bags, luggage, livestock. But why “goat?” As usually, there are two legends. The first says that an Englishman saw the colorful bus and was amazed at how cheap it was to ride. He said “cheap bus” but the locals thought he said “chiva.” The second legend is that 50 years ago the locals had no money to ride the bus so they paid with goats (a chiva).

And when I say the chivas are brightly colored, boy do I mean it. They are painted in yellow and blue and red, the colors of the Colombian flag, both inside and out. They are also covered in and out with local designs and figures. The benches inside are made or wood and there are no windows, only openings for each row of benches. Once in, you are committed to that row.

I was trying so hard to get a good picture of one. We thought we would see them on the road, and each time I tried to get a good picture. But Gustavo and Martha’s house was right on the Chiva route. Then Juan Carlos said the magic words. “Want to ride on one?” YES. Of course I did. We ran out to the road, flagged it down as it was coming around the bend, and climbed on.

What a ride. First of all, it was just as colorful inside as out. Not just the bus, but the people. They were young and old. This was their life and their transportation, but it was clear to everyone how happy I was to be there with them.

And rough?! It was hard to keep the camera still enough to take pictures. The Chiva clearly does not have shock absorbents. But it was so much fun. There was one young man who would climb from row to row, on the outside, to collect the few coins. He would tell the driver when to stop and help people on and off (at least he helped me). And we rode it all the way back to our hotel, off the main square. This may have been one of the highlights of the whole trip!

Leave a Reply