Greenwich or Where Time Began

July 18, 2017

I had a few free hours while in London for work. So at the recommendation of a friend, I decided to take the tube over to Greenwich to learn all about the Meridian, and of course to stand with one foot in each hemisphere.

I was staying at the ExCel, which seems to be at the ends of the earth as there is nothing here. But it is convenient to the tube. I boarded at Prince Regent knowing I would change at Poplar and head south to Greenwich. As is usual with the London tube, some trains don’t quite go the full destination. So I had to change trains again at Canary Wharf. But I made it to Greenwich, got off the train, and tried to figure out where I should go.

There was a map at the bottom of the station stairs, but I still couldn’t figure it out. So I went next door to the Novotel hotel and asked the concierge there. He graciously gave me a map and showed me the way to go. It was mid-day, hot and the walk is primarily up a big hill. So I took a black taxi instead. Cars are not allowed to drive through the park, but the driver went around the park which gave me an opportunity to see the town of Greenwich.

Greenwich

Greenwich is a delightful place to visit. There are flowers everywhere, and lots of large green spaces. Turns out the during the plague, many of the bodies were buried here and so nothing is allowed to be built on top of the mass graves, which accounts for at least one of the large green empty spaces.

The Big Red Ball

The taxi dropped me off right at the observatory, and I quickly went in to get my ticket. I say quickly because I wanted to be there by 1 o’clock to see the ball drop. No this isn’t New Year’s Eve in Times Square. This is the big red ball which every day at at 12.55, rises half way up its mast. At 12.58 it rises all the way to the top. At 13.00 exactly, the ball falls, and so provides a signal to anyone who happens to be looking. This is how the astronomers could send the mariners the correct time so they could set their chronometers. And anyone that could see the ball could also set their watches. So that bright red Time Ball on top of Flamsteed House is one of the world’s earliest public time signals, distributing time to ships on the Thames and many Londoners. It was first used in 1833 and still operates today. Or does it….

After buying my ticket, I walked into the outer courtyard where the very first sight is a dolphin sundial, with the points of the two dolphin tails being the pointer for the time.

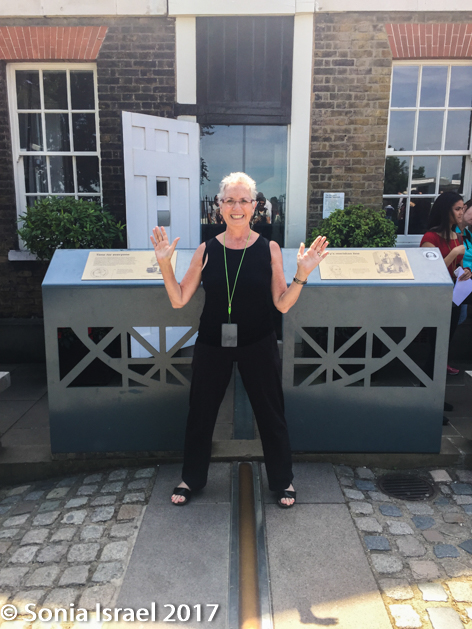

I stopped at the audio guide booth. Audio guides are free, available in lots of languages, and add a lot to the visit. But I didn’t follow the route suggested. Instead I immediately got on line to get my picture taken straddling the meridian line.

The Meridian

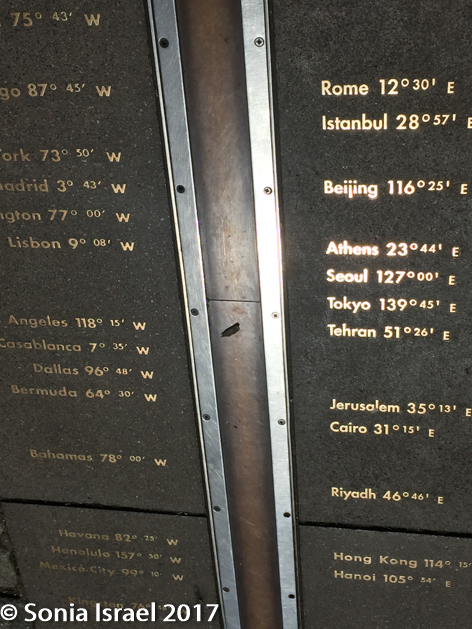

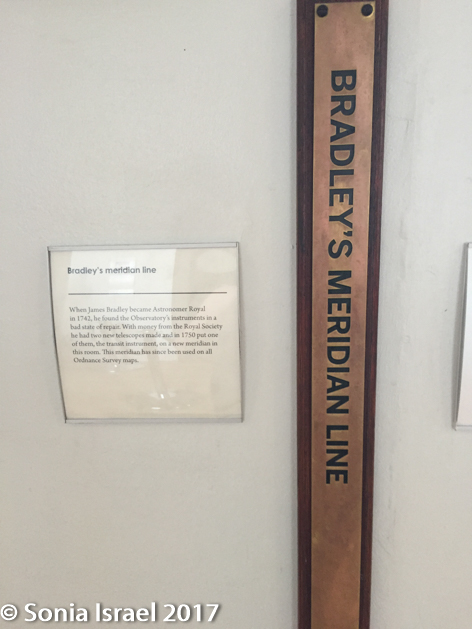

What is the meridian? A meridian is a north-south line selected as the zero reference line for astronomical observations. By comparing thousands of observations taken from the same meridian, it is possible to build up an accurate map of the sky. The line in Greenwich represents the historic Prime Meridian of the World – Longitude 0º. Every place on Earth is measured in terms of its distance east or west from this line. The line itself divided the eastern and western hemispheres of the Earth – just as the Equator divides the northern and southern hemispheres. Before this, almost every town in the world kept its own local time. There were no international conventions which set how time should be measured, or when the day would begin and end, or what length an hour might be.

The meridian line is in a cobblestone courtyard and the wait can vary from a few minutes to over an hour. The line didn’t look that long to me so I thought I better get on line before it got even longer.

The meridian line is in a cobblestone courtyard and the wait can vary from a few minutes to over an hour. The line didn’t look that long to me so I thought I better get on line before it got even longer.

The Big Red Ball – Part 2

And from the courtyard, there was a great view of the red ball. At this point it was a few minutes to one, so all of us in line looked up to see the ball move. And we waited. And we waited. And we waited. At 1:05 I figured I must’ve been wrong, maybe it doesn’t go at 1 o’clock every day, maybe it’s not the right ball. Maybe there’s another ball that was at 1 o’clock. Oh well I guess I missed it. But that story wasn’t over yet.

there was a great view of the red ball. At this point it was a few minutes to one, so all of us in line looked up to see the ball move. And we waited. And we waited. And we waited. At 1:05 I figured I must’ve been wrong, maybe it doesn’t go at 1 o’clock every day, maybe it’s not the right ball. Maybe there’s another ball that was at 1 o’clock. Oh well I guess I missed it. But that story wasn’t over yet.

So I moved along in the line, waiting my turn to straddle the meridian. After about 20 minutes I reached the top of the meridian line and could see the marks of each major city and its Greenwich time. The sun was overhead so the shadows were wicked and made taking pictures difficult. But that didn’t stop any of us. I finally reached the head of the line, put one foot on the eastern hemisphere and one foot on the western hemisphere and had my picture taken. It sounds so simple. But it was actually quite exciting.

The Flamsteed House

I retraced my steps and made my way into the Flamsteed house to see and learn about the man that catalogued the stars. Flamsteed was hired by the King Charles II to catalogue the stars in an attempt to find longitude and thus keep ships safe and on time. The house was designed by Christopher Wren (who was also the architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral) and the high point of the house was the octagon room. You walk in and it almost takes your breath away. There are tall large windows, a high ceiling, and so much beautiful light. And then there are clocks all around the room.

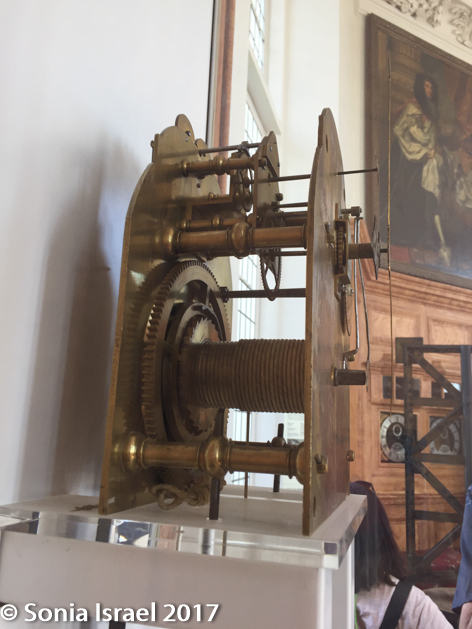

Now I should mention that I love clocks. Clocks are about time. Clocks are about moving forward. Clocks are about our bodies which have their own internal clocks. So yes I love clocks. And all the clocks in this museum were fabulous.

The room was designed so that the Astronomer Royal, in this case Flamsteed, could observe celestial events in the night sky. And that is why it has these beautiful large windows. But, in order to save money, King Charles II had the house built on some standing foundations and none of the walls, and thus none of the windows, were aligned with the meridian. So Flamsteed couldn’t measure the position or the movement of the stars. Rather, he built a hut nearby from where he made all his measurements. By the way, the beautiful wood paneling all around the room is actually painted plaster – another way King Charles II saved money.

Oh, and there was a lovely view of the planetarium from there.

Oh, and there was a lovely view of the planetarium from there.

The Big Red Ball – Part 3

About halfway through my self-guided tour, I heard an announcement that they would be a official tour at 1:30. I decided to skip the rest of the Flamsteed House and head outside to join the tour. Why not learn as much as I could? When I got outside I looked up and saw that the Big red ball had indeed come down. I met our guide Sally, and ask her about the ball. Her response was that it got stuck today and someone had to come fiddle with it to get it to go down. That should give me a lot of confidence about how accurate the world clock is! Today, as I write this, the notice on the webpage announces that the ball is out of order due to weather.

Jim Harrison

Sally led us on a one-hour tour throughout the building. And she was fabulous. We learned all about Flamsteed, Halley and Jim Harrison, who is really the one who helped perfect the longitude lines.

There is a long story about John Flamsteed, and his archenemy Edmond Halley (from Halley’s comet). But here is the very abbreviated story about Jim Harrison, a story that I found much more interesting.

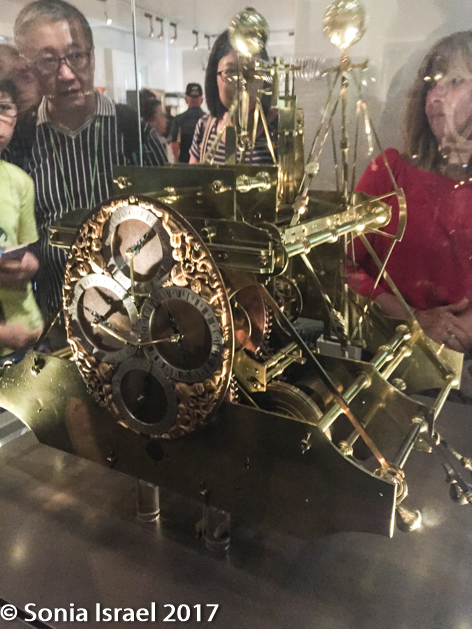

As the stars were being cataloged, it became clear that each 15° of longitude is equivalent to a difference in time of one hour. In theory then, in order to find out how far east or west he was from his homeland, all a sailor had to do was determine his local time from observations of the sun or stars and compare it with the time back home at the same moment. But obviously in the 1500’s sailors had no idea what time it was anywhere. This is where Jim Harrison comes in. A Board of Longitude was organized and they were offering £20,000 (equivalent to £2.84 million today) to anyone that could built a clock that would survive a ship’s voyage. Harrison was a carpenter and clockmaker well known for his excellent clocks. He built his first clock at age 20, made entirely of wood which was not an unusual material for a carpenter to use. Now he was going to try to build a clock that would withstand the effects of temperature, pressure and humidity as well as the corrosion of salt air. It would have to keep time of the reference place and remain accurate over long time intervals. And it had to work on board a constantly moving ship.

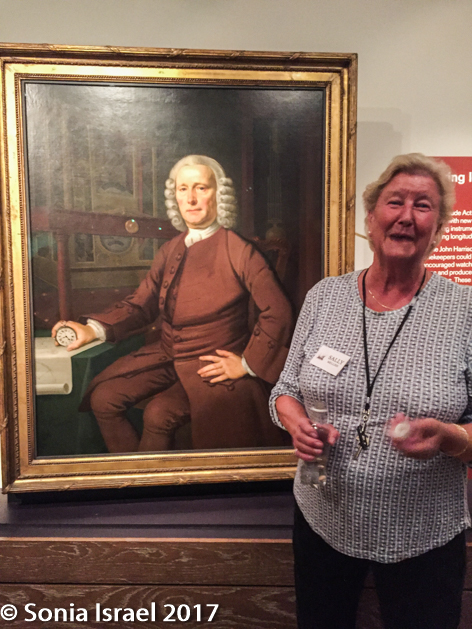

The story continues and has many twists and turns, but in short, it took Harrison over 30 years to build the perfect clock. But eventually he did it. Sally told us this story w hile showing us the actual clocks built by Harrison. She told the story with such flourish that she made it come alive. So much better than the audio guide! She ended saying that Harrison was her hero, so I took a picture of her and her hero.

hile showing us the actual clocks built by Harrison. She told the story with such flourish that she made it come alive. So much better than the audio guide! She ended saying that Harrison was her hero, so I took a picture of her and her hero.

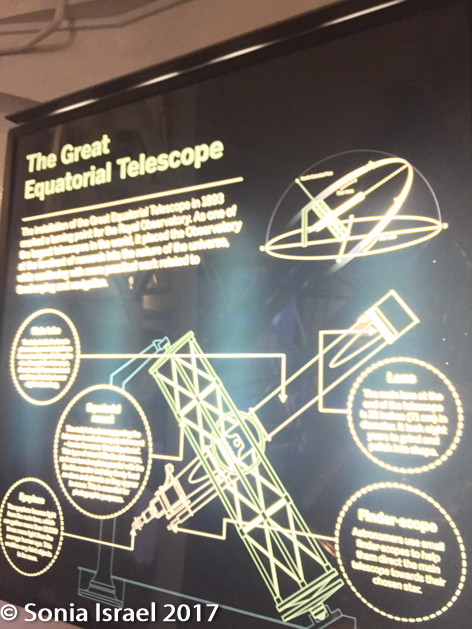

When is the tour was over, I wandered around some more looking and learning about the different meridian lines (until the prime meridian was chosen), the different telescopes used to find longitude and the stars. I walked over to the gift shop where I noticed stairs leading up to the big, big, big equatorial telescope which is used to study the planets.

And right outside the gates, where everyone can see it, is the  Shepard 24-hour gate clock. This was installed in 1852 and was one of the first electrically driven public clocks. The dial always shows Greenwich time. This means that in summer, when Britain changes it clocks to British Summer Time (BST), the clock seems to be one hour behind. The clock is accurate to 0.5 seconds.The other unusual thing about this clock is that it is in 24-hour time which means noon is at the bottom and midnight is at the top.

Shepard 24-hour gate clock. This was installed in 1852 and was one of the first electrically driven public clocks. The dial always shows Greenwich time. This means that in summer, when Britain changes it clocks to British Summer Time (BST), the clock seems to be one hour behind. The clock is accurate to 0.5 seconds.The other unusual thing about this clock is that it is in 24-hour time which means noon is at the bottom and midnight is at the top.

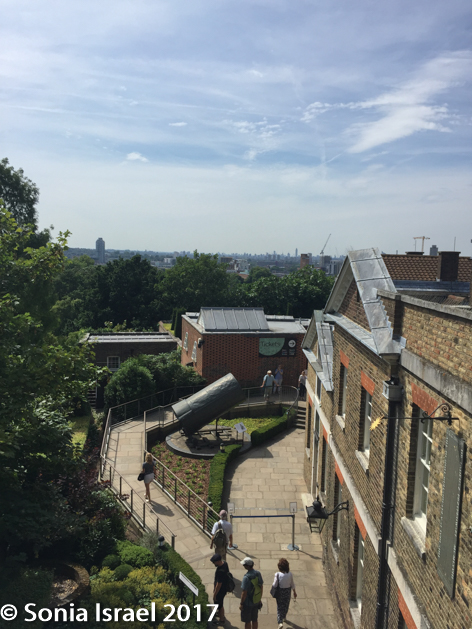

And since we were on the top of a hill in Greenwich Park, the views were great.

The Tube to Greenwich

It was then time for me to head back to my meeting.

I walked down through the park, which was full of flowers and where families and couples were picnicking and enjoying the beautiful weather, towards the Maritime Museum and the Queen’s House, stopped for an ice cream, walked out St. Mary’s Gate, down Nevada Street, right on Stockwell Street, and left on Greenwich High Road, right back to the tube. Examining the map, it became clear that a quicker way would have been to get off at the Cutty Sark Station, turn left onto Church Street which turns into Greenwich High Road and then into the park. But if I had gone that way, I would have missed the three-story junk store, called The Junk Store along the way. I could have spent hours there if I didn’t need to get back to work.

All in all, it was an amazingly interesting and fun afternoon.