Day 6, Monday October 24, 2016

Black Taxi Tour of Belfast

We had visited the Peace Wall and Wall of Murals briefly as part of our tour. But Thea and Steve and Andy and I had talked about taking a black taxi tour of Belfast that afternoon. These are tours that take place in the old London black taxis, driven by “survivors” of the Troubles, who tell their stories of their first hand experiences. Part of me felt like we had already seen the Peace Wall etc, but part of me wanted to hear more stories. But we decided not to go. Then Dan mentioned that he and Jean were going and Andy and I decided to join them after all. And were we glad we did!

The hotel arranged it for us and in just a few minutes a black taxi pulled up. Our driver/gui de was Peter. The taxi had a bench in the back for two and two seats that pulled down, facing backwards. We climbed in and off we went. And here you have to know the rest of the history, the history of the Troubles. I remember hearing about all the bombings in Belfast, but everything we heard was from the British, Protestant side. Now we got to hear the other side.

de was Peter. The taxi had a bench in the back for two and two seats that pulled down, facing backwards. We climbed in and off we went. And here you have to know the rest of the history, the history of the Troubles. I remember hearing about all the bombings in Belfast, but everything we heard was from the British, Protestant side. Now we got to hear the other side.

Wall of Murals or the International Wall

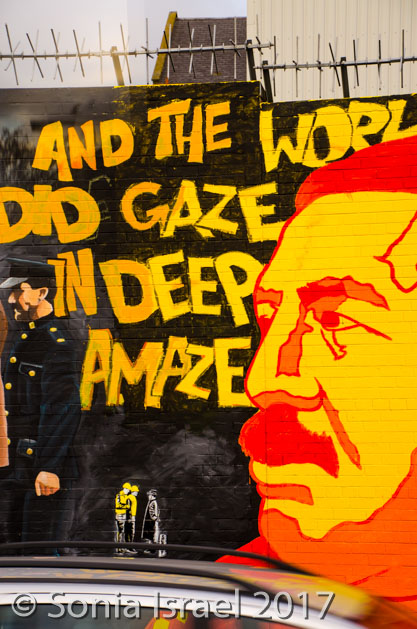

The tour began with the wall of murals, officially called the International Wall. As I mentioned earlier, our bus tour had stopped by here this morning, briefly, for pictures but not much explanation. Peter, our guide, told us how the murals on the wall are changed every few months depending on what discrimination is going on in the world. It is an International wall and some of the murals change monthly by people from other conflicts who move here. For example, there was a mural for the shooting that recently took place in the gay bar in Orlando. Each drawing has to be submitted to the officials, and approved before it’s allowed to be applied to the wall. They’re very careful to prevent hate crimes and hate inspired messages. This wall is about peace and tolerance and acceptance.

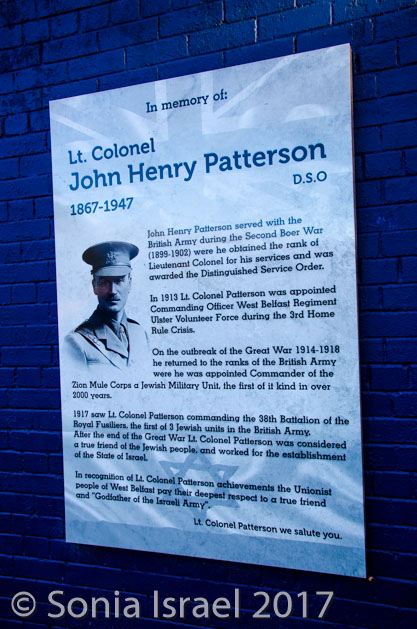

But the majority were about Ireland. These murals have become symbols of Northern Ireland as the depict past and present political and religious divisions. Since the 1970’s there have been a about 2000 murals both in Belfast and in Derry (which we would visit tomorrow). Some depicted the 1981 Irish hunger strike, with emphasis on Bobby Sands, the leader. There were murals of international solidarity with revolutionary groups from around the world. There was a mural of Mandela. And one of in solidarity with the Palestinians. But the one at the end, which was quite large, was in honor of Lt. John Henry Patterson. I had never heard of Lt. John Henry Patterson. But I couldn’t miss the Israeli flag. So here is the rest of the story.

Lt Colonel John Henry Paterson

Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson was a British soldier and a great Christian Zionist. During WWI, he served in West Belfast regiment of the Ulster Volunteers during the Home Rule Crisis of 1913-14. Although he himself was Protestant, he became a major figure in Zionism as the commander of the Zion Mule Corps and later in the 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, also known as the Jewish Legion, which was described as “the first Jewish fighting force in nearly two millennia”, and the godfather of the modern IDF (Israel Defense Forces). During his time in command of the Jewish Legion, Patterson was forced to deal with extensive, ongoing anti-Semitism towards his men from many of his superiors (as well as peers and subordinates), and more than once threatened to resign his commission to bring the inappropriate treatment of his men under scrutiny.

After his military career, Patterson continued his support of Zionism. He remained a strong advocate of justice for the Jewish people as a promoter of a Jewish army to fight the Nazis and to stop the Holocaust. He was a member of the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe. During the Second World War, while he was in America, the British government cut off his pension, arguing they had no way to securely transmit his funds to him. This left Patterson in severe financial difficulty. Just the same, he energetically continued working toward the establishment of a separate Jewish state in the Middle East.

Patterson was close friends with many Zionist supporters and leaders, among them Benzion Netanyahu, Bibi’s father. Bibi’s brother, Yonatan, was named after him.

During the 1940s, Patterson and his wife, “Francie” lived in La Jolla! One of his final wishes was to be interred in Israel ideally with or close to the men he commanded. This finally happened in 204 when his remains, along with his wife’s, were re-interred in Israel where some of his men were also buried. As the interment, Netanyahu referred to Patterson as “the godfather of the Israeli army” and “a great friend of our people, a great champion of Zionism and a great believer in the Jewish State and the Jewish people…“

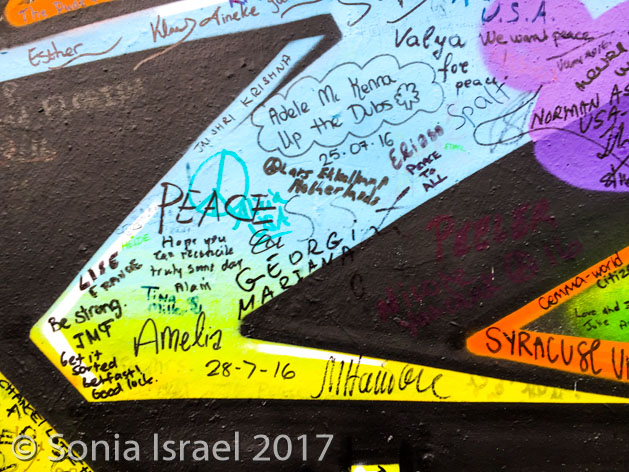

The Peace Wall

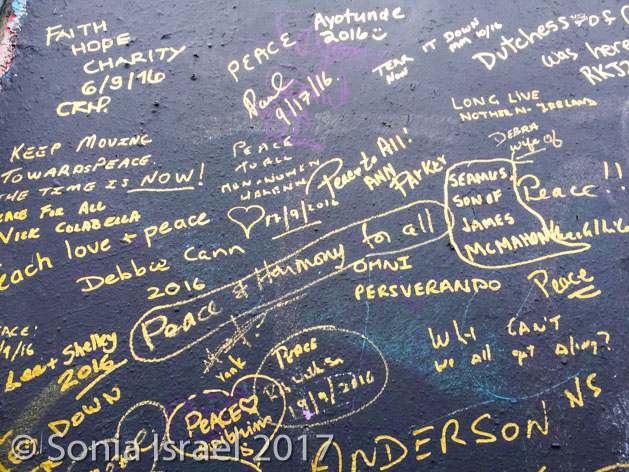

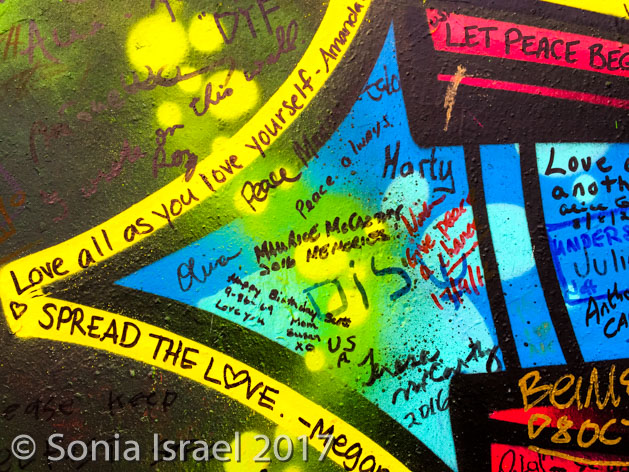

After walking the full length of the mural wall, and hearing all the stores, we got back into the cab and headed to the Peace wall. We had been here earlier as well, and I got to write a message. But we never heard the full story until now.

The rest of the story…

In 1920, Ireland was divided into two countries, The Republic of Ireland (Southern Ireland) and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland had 6 counties in it, the 6 with the largest Protestant populations, loyal to Great Britain and the Queen. And it is in Northern Ireland that the Troubles began in the late 1960s. This was really an “ethno-nationalist” conflict, also called a guerrilla war. The conflict was primarily political and nationalistic and was fueled by historical events. A key issue was the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. The Protestants who were unionists and loyalists, considered themselves to be British and wanted Northern Ireland to remain within the UK. The Irish Nationalists/Republicans were mostly Catholics, considered themselves Irish and wanted to leave the UK and join a united Ireland. But as Peter told us, it was really a fight between the Protestants and the Catholics. They had been living together, or “tolerating each other” as Peter said. The Catholic families had lots of children and therefore tended to be poor. The Protestants had fewer children and were wealthier. And although not as bad as the Penal Laws of earlier times, the Catholics were still being discriminated against. There was job discrimination with Catholics having a harder time getting certain jobs, especially in the government. They were not allowed to use their own language (Irish). Only the head of the household could vote. They weren’t allowed to worship. He explained how the Catholics all had lots and lots of children, often more than 10, and so they lived in poverty. The Protestants on the other hand had fewer children and therefore had easier lives. There was housing discrimination. The was voting discrimination – only one Catholic household member could vote in local elections whereas the in the Protestant households, everyone of voting age could vote. And there was much gerrymandering which allowed the Protestants to have more clout. So the conflict was about civil rights. And the time came to fight for their civil rights.

The Burning of Catholic Homes

Then in one night, the Catholic homes were all burned. The Catholics had to barricade themselves to protect themselves. About 40,000 Catholics were displaced and became refugees, leaving Ireland all together, moving to Scotland, or other parts of the UK, or the United States. And many never returned. Peter’s own family were refugees. He was one of 14 children, and at the age of nine was sent in Belfast to an orphanage with other displayed children. His different siblings were all farmed out to different homes, and to try to save them and make sure they had food. He was lucky as he was back with his parents only a few months later. He only went to school until age 15, and then had to go to work in a bakery, to help support his family. To this day he is still very bitter about the Protestants and the British.

So the Catholics were discriminated against by the Protestants and by the police force. Violence ensued and the British Army was sent over, full of very young men who had no idea what they were getting into nor who understood what the conflict was about. The British Army felt it was neutral and was just trying to uphold the law and order in Northern Ireland, and this is what we heard in the news back then. But the Nationalists felt they were under occupation.

During this time the city center of Belfast was surrounded by a fence. Each person coming in and out was stopped and searched. Cars were searched. No car was allowed to be parked unattended. When I asked our walking tour guide about it, he said, “You get used to it. You open your bags when entering a building.” And it all becomes part of your new norm. Most of the violence took place in the city as that was where the commerce was and they wanted to make the resistance felt economically. But there was also violence in the neighborhoods including a number of Catholic homes, schools and businesses. Much of it took place in the Shankill area. In all, more than 3,500 people were killed in the conflict, of whom 52% were civilians, 32% were members of the British security forces, and 16% were members of paramilitary groups. In this area, at the time of the Troubles, if you went into a pub, you would be asked if you have a gun. If you said no, they asked if you wanted one.

The walls are built

A series of walls were built as barriers that separated Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods, 42.5 miles of wall! And these are the Peace Walls. The Peace Walls, also called the Peace Lines, range in length from a few hundred yards to over three miles and are 25 feet high, and are made of iron, brick, and/or steel. Some have gates in them which are still closed between 600PM and 600 AM keeping people in, or out, depending on how you look at it. When built in 1969, they were meant to be temporary. Today 30 walls still stand, thus called the Peace Walls. But in reality they still separate the neighborhoods.

Peace…finally

The conflict lasted almost 30 years, until 1997 when a peace agreement was finally signed. And when peace was finally reached, one part of the Agreement was that Northern Ireland will remain within the United Kingdom unless a majority of the Northern Irish electorate vote otherwise.

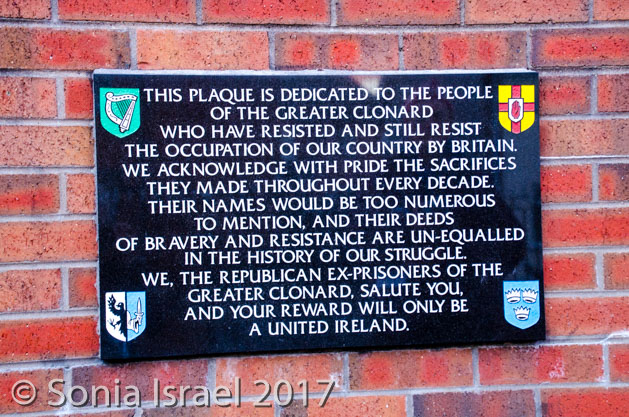

The Catholic “Volunteers”

On the other side of the wall, in the Catholic sector, were memorials to the “volunteers” who were killed in the conference. Many were just children, 13 or 14 years old. But they all fought for what they believed in, which was civil rights for themselves and their families and their countrymen. It was called the “niceness Catholic Republicans of North Ireland vs the Shinkill Protestants. On the gates of the memorial was a Phoenix rising from the ashes. Yet the homes facing the wall still had security grills on the windows, to protect them from flying bullets and bombs. New families remove them, but the old families still have them. Long memories.

As we stood within the gates of this memorial, a young girl, around 6 or 7 came to explore who these strangers were. She was in her school uniform, long blonde hair and a bright pink down jacket. And she swung on the gates back and forth back and forth. To her this is a playground. When she gets older she’ll understand what this means. Right above her is a large billboard with the photograph from the newsreel. And on it it says Bombay Street, never again! (Bombay Street is where some of the fighting began with Catholics barricading themselves with buses etc to protect themselves.) For me of course it was so reminiscent Shoah. I think we coined that phrase, never again. But it sure applies to so many conflicts around the world.

And the sun began to set. The sky was spectacular. The past horror of the area was being replaced with the beauty of today. But oh so slowly.

Why are there still walls?

When I asked Peter why the walls were still up and why the gates were still closed, he replied that the old guard still felt they needed, and wanted, that separation. But in the last election the new generation was voted in and he was confident that within 4 years, things would change. Perhaps one day it will be like the Berlin Wall. Parts need to remain up for the history, but not miles and miles of wall.

The Police Station

It was starting to get dark, but Peter said there was one more place he wanted to ta ke us. We drove a few blocks and stopped at a huge red brick building that took up about 2-3 square blocks, half a mile long. It looked like a prison, but is now a part time Police Station. It essentially stands empty. Peter was very bitter that it sat here empty when it could be converted into homes and commerce to help the growth of the community.

ke us. We drove a few blocks and stopped at a huge red brick building that took up about 2-3 square blocks, half a mile long. It looked like a prison, but is now a part time Police Station. It essentially stands empty. Peter was very bitter that it sat here empty when it could be converted into homes and commerce to help the growth of the community.

It was a powerfully emotional afternoon. Listening to Peter we began to understand the other side of the story, the side other than what we heard on the nightly news. I felt more educated. I felt I understood more about the conflict. I was so glad we went. Glad we went to Belfast. Glad we took the Black Taxi tour. I asked him lots and lots of questions. And I got answers, at least from his perspective.

We were exhausted but still had to eat dinner, so we had Peter drop us off at the Robinson Pub. We took pictures together and hugged and said good-bye.