August 11-19, 2019

Pantanal

Most people have never heard of the Pantanal in Brazil. Some of you may recognize it from John Grisham’s novel, The Testament, which takes place mostly in the Pantanal. When I mentioned I was going to the Pantanal to look for jaguars, I was asked if they were cheaper down there! But no. The Pantanal is known not for the car but for having the largest number of jaguars in the world. So we hoped there would be a good chance of seeing at least one.

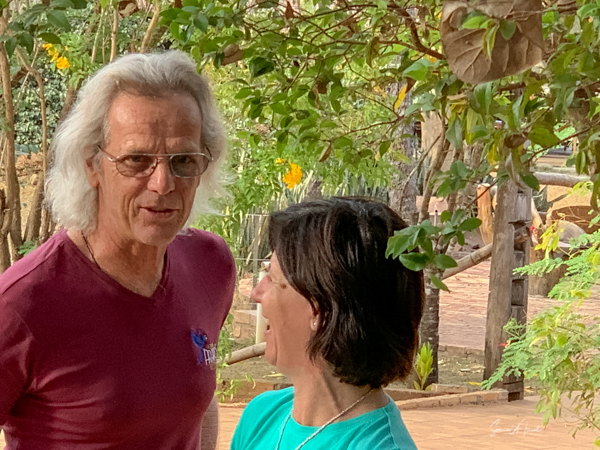

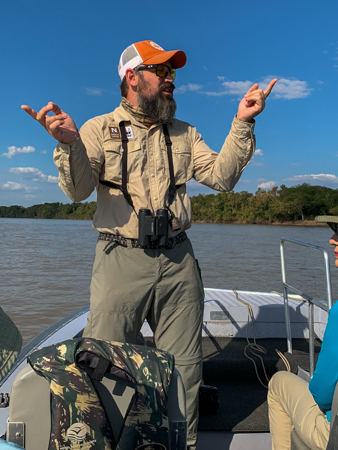

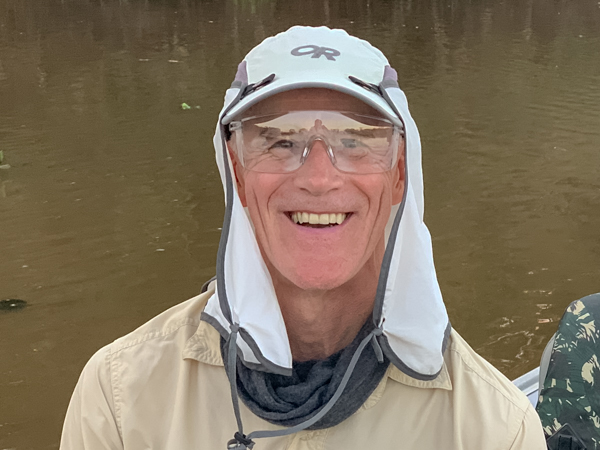

We were 11 intrepid travelers going on this trip with Natural Habitat. Cassiano (Zapa) Zaparoli was our amazing guide and my fellow travelers included (in no particular order) Ruthi, Debra and David, Cindy and Richard (Dick), Carol and Gary, Johanne and Mario, and Karl. Some of the group knew each other as they had traveled together, with Zapa, in Patagonia. The rest of us met in Rio, but by the end of the trip, were one big family.

- Ruthi

- Debra

- David

- Cindy

- Richard

- Carol

- Gary

- Johanne

- Mario

- Karl

- Sonia

- Zapa

Before I launch into the heart of my story, let me say that this post is a bit different from my others. Those of you who follow my travels know that I often separate my posts by city or by day. This one has all 9 days and all the places we visited in one post. Why? Because this is really about the animals so it made more sense to keep it as one long story. In addition, while the photographs are mine (except for a handful), many of the videos were taken by Ruthi and my other compadres (thank you all for sharing). And I included lots of videos. They help you hear and see and almost feel what we experienced.

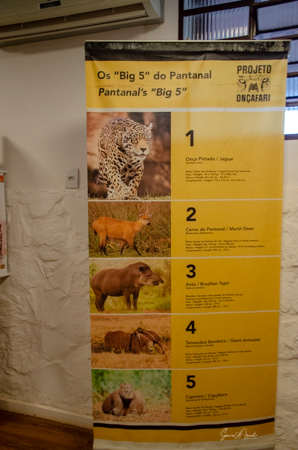

What exactly is the Pantanal?

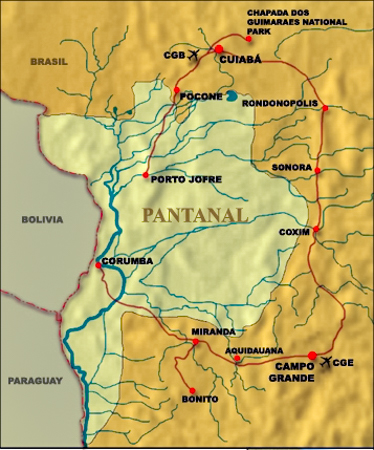

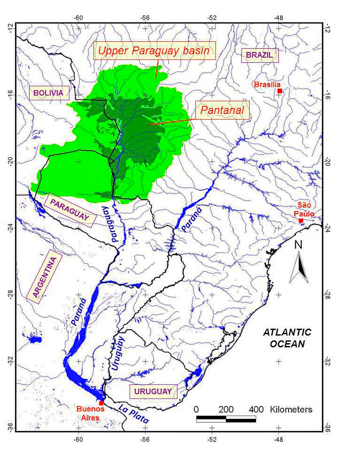

The Pantanal is right in the center of South America and is divided into the Northern (Mato Grosso) and Southern (Mato Grosso do Sul) Pantanal, both of which we got to visit. Each is different, with their own distinct characteristics and their own animals who call it home. The North is full of jaguars, giant otters, ocelots, caimans, capybaras and birds, birds, birds. The South also has jaguars (although fewer of them), caimans, capybaras, but also has armadillos, giant anteaters, tapirs, 4 kinds of deer, peccaries, and birds, birds, birds.

Pantanal comes from the word “pantano” which means swamp in both Portuguese and Spanish. One could think of the Pantanal as a swamp, but really it is the world’s largest freshwater wetland with one of the most diverse and spectacular ecosystems in the world. And it has the highest concentration of wildlife in all of South America – more than the Amazon. There are 698 species of birds, 80 species of mammals, 26 of fish and 50 of reptiles. The area itself is 70,000 square miles. Much of the Pantanal has been named a national park by the UNESCO World Heritage. In fact, the Pantanal is a combination of national parks and privately-owned lands.

The Pantanal is one of eight biomes in Brazil. The others are the Amazon, the Cerrado (vast tropical Savannah), the Caatinga (desert vegetation), Paraguayan Chaco (a semi-arid region), the Atlantic Forest, the Pampa (or Southern Fields) and the Coastal. In general, the North and the South are very dry. The West is a Savannah. The Central portion is very pristine and clean; in fact, as told to us by Zapa, our wonderful guide, it is one of the most pristine places on the planet, “the way the earth was created.”

And of those seven biomes, the Pantanal has elements of five of them – the Cerrado, the Amazon, the Atlantic forests, the Paraguayan Chaco, and Caatinga. The Pantanal area is characterized by a top layer of sandy soil over clay. It is not good for agriculture so the farms that do exist are mostly cattle farms. When it rains, the rains descend in a torrent but do not permeate into the ground, so flooding is widespread and deep. Since this area is very flat, the water from the rivers rise and combine with the waters of the lakes, creeks, and marshes and all of them then merge with the Rio Paraguay to form one large fresh water sea. When the water recedes, the land is renewed and fertilized.

A time to go, a time not to go

And for that reason, there is a time to go and a time not to go. In the dry season, from May to September, the Pantanal is a flat grassland covering an area about the size of half of France. There are lakes and woodland and one can see the tracks of the animals weaving between them. But in November-March, it is the rainy season with the water level rising and flooding the whole area.

Zapa said, “In November the rains are very hard, and the bugs can carry you away.” We were here in August and the weather was perfect, not cold (except sometimes at night), not too hot (except sometimes in the middle of the day), dry and no bugs (although we still sprayed for them).

Unlike the Amazon, no indigenous folk live here. Just the animals, the birds and the isolated cattle farmer or two. And the people who work in the Ecolodges. The funny thing is that most of the tourists are not Brazilian. The Brazilians go to Africa for safaris, but they miss the safari of the Pantanal. The Brazilians who do come to Pantanal, come for recreational fishing, not to see jaguars.

Northern Pantanal (Mato Grosso)

Day 1, Sunday, August 11, 2019

Our first few days were spent in the Northern Pantanal. Due to an unforeseen hiccup, the group left Rio on Saturday, August 10, 2019, but I did not join them  until Sunday. I flew with Azul Airline from Rio to Belo Horizonte, and after a quick layover, continued onto Cuiaba. We flew over lots of empty green land. And mines. But we saw very few homes or villages.

until Sunday. I flew with Azul Airline from Rio to Belo Horizonte, and after a quick layover, continued onto Cuiaba. We flew over lots of empty green land. And mines. But we saw very few homes or villages.

A side note on Azul Airline. Azul in Portuguese means blue, and the airline was named after a naming contest. It was started by the founder of Jet Blue, so the theme continued.

Once we arrived in Cuiaba, I got to see my first Jaguar. Ok, ok, so it wasn’t a real jaguar, but it got me excited about the upcoming adventures.

Eugenio Souza, my very own private Natural Habitat guide and I were met right outside of arrivals and the trip officially began. We stopped for lunch right in town at Sinuelo, a combination restaurant, take-out and souvenir shop. And I did buy some gifts there. Although there were lots of tables and chairs awaiting us, we decided to take our sandwiches to go in order to save time. I was anxious to rejoin the group. The menu looked great and we each chose our sandwiches. The waitstaff was busy in the kitchen but brought out glasses of homemade berry juice for us to try. It was delicious, as were the sandwiches. After a brief wait, we got our lunch and hit the road. We drove through small towns, many of which were shut tight as it was Sunday and this is a Catholic country. We did make a brief bathroom stop one hour into the trip at Pocone, a small town of 5000 people. I think its claim to fame is that it is on the route to the Pantanal. But it had a clean bathroom and a fancy restaurant/gift shop. I did notice when I stepped out of the car that the road was this red dirt and everything was covered in red dust.

And we were so lucky. The rest of the group had arrived at night, so they didn’t get to see much. But I got to see so many things. We passed lots of statues of the local animals. Jaguars. jabirus, hyacinth macaws, giant otters, capybaras, caimans (see below to learn more about all of these). All the animals who are native here. And everyone seemed to want statues of them. (As an aside, once I returned home, I tried to find a statue of the Jabiru for my backyard. No such luck). But we also saw the real things. We passed a group of capybara in the water. We passed a Jabiru up in its nest. We saw a huge caiman who looked almost like a statue as he never moved the entire time we watched him. We saw Brahmin cows who looked so skinny and bony. We saw birds perched and birds flying. There was a green Ibis. There were cattle egrets sitting on top of buffalo. There was a kingfisher sitting on a wire. Muscovy ducks. Snail kite (a kind of hawk who hovers like a kite).

- Capybara

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Termite village

- Caiman

- Caiman

- Water buffalo

- Great Egret

- Green Ibis

- Kingfisher

The Candelabra Tree

In addition to all the wonderful birds and animals, there were trees of all types everywhere. The most beautiful was a tree that was in full bloom with yellow flowers. Only later did I find out that it is called the Candelabra tree, a perfect name for this tree as the yellow flowers all faced up just like candles. It can grow up to 100 feet and the branches grow in a circle around the stems. As the tree grows and matures, the lower branches drop off, leaving a long, bare trunk with a crown of upturned branches tufted at the ends. Thus, a candelabra.

The tree is actually a parana pine, also called araucaria or Brazilian pine. And although called a pine, it really is not in the pine family. The wood is used for veneer, furniture, and flooring, and therefore has been heavily exploited in the past. And thus, although we saw it everywhere, both in the north and south, it is a critically endangered species.

Zapa later told us that their season was almost over, so we were lucky to see them in bloom.

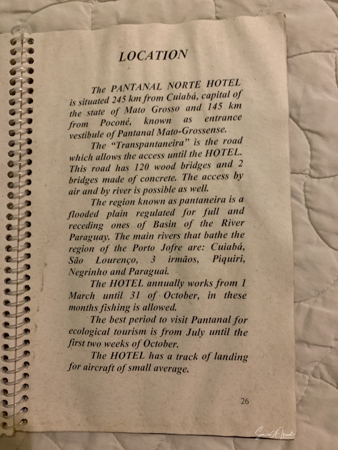

The Transpantaneira Highway

The paved road ended and the Transpantaneira Highway began. Although called a highway this is really a red dirt road originally built in the 1960’s by Brazil’s then militarized government to transport the Brahmin cattle to the meat-processing plants in the south. It was originally supposed to go all the way to Corumbá, but 93 miles later, when they reached Porto Jofre on the Rio Cuiaba, that plan was aborted. The earth that was cleared away for the highway’s construction left large holes that have become ponds, canals, and lagoons which now attract all sorts of wildlife. The road goes through savannas, marshes, and forest patches. And it has over 122 (more or less) wooden bridges. We were only going part of the way today, but would end up driving the rest of it in a few days.

Close to the start of the Transpantaneira Highway was the famous “Here begins the Pantanal” sign. We stopped to take some pictures. Now it was official. I was here.

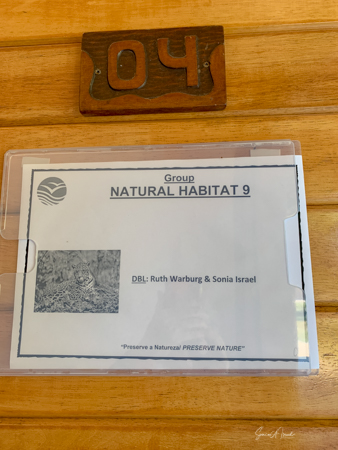

Araras Pantanal Eco Lodge

After a trip of about two hours covering 80 miles, we finally reached the Araras Pantanal Eco Lodge. We drove up and were greeted by a capybara, Zapa and Ruthi, a wet towel and a glass of Barbados berry juice. Andre Thuronyi (who is Hungarian) and Jerneja Akhila Krusic (who is Slovenian), the owners, also greeted me as they do each guest on arrival. Ruthi walked me to our room and there was a bottle of champagne on ice and some flowers, sent by Natural Habitat, to welcome me.

Araras Pantanal Eco Lodge, which was one of the the first eco-lodges in the Pantanal, was built to be in perfect harmony with the beautiful surroundings. It is a self-sustainable lodge with its own private trails in the forest, wooden walkways over the wet areas and lots of birds. There is also a swimming pool. They offer guides and canoeing and horseback and safaris, but we had our own and didn’t need to use theirs. Breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea and dinner were all included, but I only got to enjoy dinner and breakfast. Dinner was in the large wooden dining room which was set with long tables and round tables for group meals which were served buffet style. Breakfast the next morning was outdoors surrounded by the trees and birds serenading us. All the food is local with the fish from the nearby river, the beef from a ranch close by, and the fruits and vegetables all grown locally. The décor is rustic but in a comfortable way, made from organic materials. Our room was very simple with two beds, some shelves and a small, but adequate bathroom.

Capybara

Since I mentioned that I was greeted by a capybara, let’s jump right into the description of them. The capybaras are ubiquitous in the Pantanal. They are everywhere both in the north and the south. We would joke each time we saw one – “Oh look! The elusive capybara!”

The capybara is the world’s largest rodent and is a relative of the agouti, chinchilla, and guinea pig. They are semi-aquatic mammals who like to live in densely forested areas but always near bodies of water, i.e., the Pantanal. Their scientific name, hydrochaeris, comes from the Greek meaning “water hog.” The name capybara comes from the word, kapiyva in the Guarani language, meaning “master of the grasses,” also translated as “lord of the fields.” Zapa told us that “they live to live.”

Adult capybaras may grow to over four feet in length and weigh up to 140 pounds; females are a little heavier than males. An adult capybara can eat 6 to 8 lbs of fresh grass a day. They also eat their own poop which contains beneficial bacteria that helps their stomach to break down the fiber from the grass. They have heavy, barrel-shaped bodies and short heads with reddish-brown fur on the upper part of their body that turns yellowish-brown underneath. When fully grown, their coarse hair is sparsely spread over their skin, making them prone to sunburn so they rokk in mud to protect their skin. They have blunt muzzles, webbed feet, and no tail, and their back legs are slightly longer than their front legs.

Capybaras reach sexual maturity within 22 months, and in Brazil, they breed once a  year during the rainy months of April and May. The male pursues a female and mounts when she stops in water. Having said that, we were in the Pantanal during a full moon in August, and we saw them mating on land.

year during the rainy months of April and May. The male pursues a female and mounts when she stops in water. Having said that, we were in the Pantanal during a full moon in August, and we saw them mating on land.

Baby capybara begin eating grass within a week of being born but will continue to suckle—from any female in the group—until weaned. Youngsters will form their own cluster within the main group. We saw lots of little ones, and while I am not a rodent fan, these were very cute.

Their big predator is the jaguar. Later in the trip, we would see several jaguars stalking the capybaras. To protect themselves, the capybaras stand around in groups, with each one facing a different direction, on the look-out (you can see that in each of the videos). When they realize how close the jaguar might be, they communicate through a combination of scent and sound such as purrs, alarm barks, whistles, clicks, squeals, and grunts. They then jump into the water where they can stay underwater for up to five minutes.

They sleep little, usually dozing off and on throughout the day and grazing through the night. If necessary, they can sleep underwater, keeping their nose just at the waterline.

Safari Drive

Once I had settled in, we were off for a four-hour afternoon drive in an open-air safari truck, mostly still on the grounds of the Araras Pantanal Eco Lodge. We entered an area that was quite reminiscent of Africa, with savanna grass, acacia trees, and jacaranda trees that sadly were not yet in bloom. But there were still lots of blooming candelabra trees.

At one point the road was blocked by tree limbs. Zapa and Chaco pulled out their machetes and hacked away. That cleared the path, but it turned out that the limbs were covered in ants which then crawled all over Zapa. He was not happy.

We saw so many birds, today and throughout the trip. See the section below for a complete list and pictures. But the hyacinth macaw gets its own section.

Hyacinth Macaws

The hyacinth macaws, the largest of all the macaws, are all over the Pantanal, living in tall trees, in palms in the swamps, in the forests and near rivers, flying everywhere, and even walking on the ground. As the name suggests, they are a bright blue with large black eyes surrounding by yellow rings, a yellow chin and a strongly hooked beak. Their feet are zygodactylous which means that two toes point forward, while the other two point backward. They are the largest of all the parrots with an average wingspan of four feet. Their long beautiful tail comprises about one-third to one-half of their length.

- Hyacinth Macaw

- Hyacinth Macaw

- Hyacinth Macaw

- Hyacinth Macaw

In the Pantanal, hyacinth macaws eat mostly nuts and little coconuts from the acrui and boucaiuva palm trees. They feed on the clusters that fall down from the tree or pick up the ones that have fallen on the ground. And they are extremely messy eaters. I can attest to that as we saw many of them eating, using their toes to hold the food. But by dropping the seeds they help regenerate forest growth. These birds are able to break open and consume the toughest nuts; their mobile beaks allow the birds to press hard seeds between their tongue and palate and grind them so that they can be digested. (For more on how they eat, please see the section below on the Southern Pantanal).

They are also very noisy, screeching quite loudly. And notice in the video that each time they cry out, they open their wings.

Hyacinth macaws gather in flocks to sleep at night but maintain a monogamous bond with mates for life. Macaws are mostly found in pairs, either in their nests or flying together; mates may even show affection by licking each other’s faces. Once paired with a mate, they are rarely found alone, except to feed, when one bird must remain to incubate the eggs.

As mentioned above in the capybara section, we were here during a full moon and on our last morning at the Pantanal North Porte Jofre (see below) we saw two hyacinth macaws mating. They sat on a tree branch, right next to each other, and you could see the males tail go up and down as they mated.

Nests are made in hollowed areas in trees, where, in the protection of the thick foliage, they are camouflaged so that predators are less likely to spot them. The clutch size is typically one to two white, rounded eggs, with an incubation period of about 29 days. After hatching, the young may stay with their parents for two to four years, during which time they are fed by regurgitated food from the male. Macaws take three years to reach sexual maturity. The parents bring them to join a group of single macaws and leave them there to breed. At that point they are as large as their parents, except for their chest feathers. Sometime later, the parents will call for their chick. If the chick does not return, it means it has mated. As mentioned, they mate for life and will breed about 6-7 times in their lives.

The hyacinth macaw population got so low in the 1980s that they were almost endangered. There are a number of conservation efforts around the country (see below for the conservation efforts in the Southern Pantanal at the Caiman Ecological Refuge), but the owners of this lodge have planted many trees that will eventually serve as homes for the birds. This will take time as the macaws build their nests on the manduvi tree and the tree has to be 60-80 years old to have hollows wide enough to hold the birds and the nest. But as the tree continues to age, it becomes fragile and vulnerable to the heavy winds during the rainy season.

The Great Potoo

At one point, Zapa stopped the car and had us all climb out. He used his green laser pointer to show us a Great Potoo. We saw a second one a few days later on the river. At first I thought it was an owl, but if you at his face carefully, you can see it is very different.

- Great Potoo

The great potoo (Nyctibius grandis) is a nocturnal passerine bird (meaning it has feet adapted for perching). Its most well-known characteristic is its unique moaning growl that it vocalizes throughout the night. We did not get to hear that.

The Great Potoo tends to perch high up in trees, and always returns to the same place. That’s how Zapa knew where to find it. Otherwise, its coloring resembles the tree stump and it is quite well camouflaged.

Zapa told us that the great potoo has a magic eye. It doesn’t open its eyes during the day because it would ruin its camouflage up high in trees. But it can see without opening its eyes. Wish we could do that!

Greater Rhea

We also saw greater rheas walking in the field, and then crossing the road in front of us. Rheas are interesting birds. They are flightless and are distant relatives of ostriches and emus. They are one of the few birds to have an actual penis. The male can mate with at least 15 partners. The male builds the nest and all of the female birds leave their eggs in the nest while the male sits on them. A few days before they are about to hatch, the male cracks open a few which attracts insects. The insects then serve as the first food for the rest of the chicks.

- Greater Rhea

Rehabilitated Parrots

But we weren’t just randomly driving. We had a destination in mind. Our destination for the afternoon was the Passo da Ema Ranch, a cattle sub-ranch belonging to the Araras Lodge. Although a working cattle ranch, it also has a mission to rehabilitate poached parrots. The birds are fed twice a day and then encouraged to return to the wild.

We came close to sunset and there seemed to be hundreds of green parrots enjoying their free meal. Many of the birds end up mating with wild parrots and then bring them back for free food. Who wouldn’t return for free food!? And of course, other birds come and hang out as well.

- Parrot and Yellow billed cardinal

- Blue fronted parrot

- Yellow billed cardinal

- Blue fronted parrot

- Bare-faced curassow

- Bare-faced curassow

Mustn’t go hungry

And speaking of food, just in case we were hungry, there were snacks for us. Zapa came out carrying a basket, reminding me of Little Red Riding Hood. Throughout the trip we had snacks of M&M type candies (wrapped in a white paper cone), nuts and raisins (best mixed with the chocolate candies), granola bars and much more.

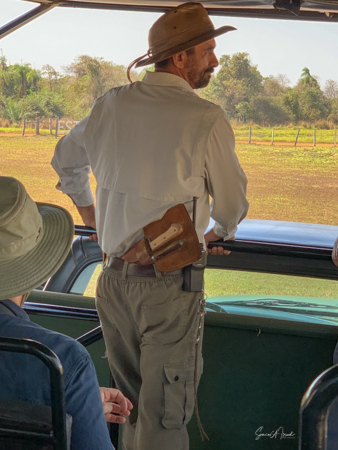

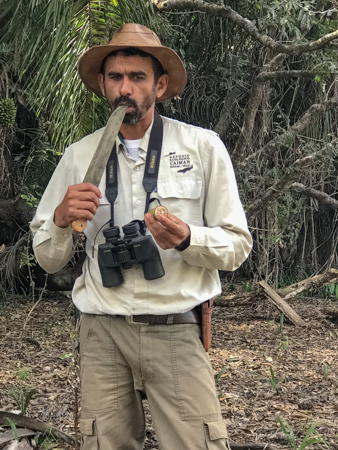

Pantaneiros

At the other end of the ranch were cowboys, Pantaneiros, learning how to lasso the cattle, both for their ranch work and for competitions. There was a man riding a motorcycle pulling a fake bull. The Pantaneiro would ride his horse behind, trying to lasso the “bull.” The experienced cowboy would lasso the horns of the bull, and nowhere else. Chaco, Zapa’s local helper guide in the north, was a Pantaneiro as was Guarano, Zapa’s local helper guide in the south.

- Chaco

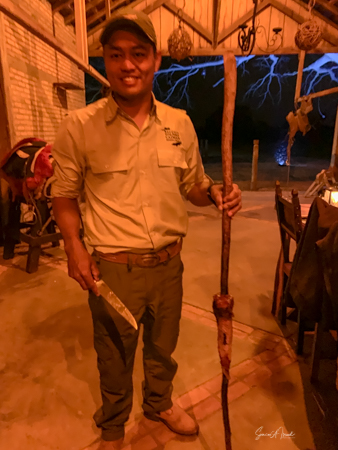

- Guarano

The cattle ranches here would not survive without the Pantaneiros. Their culture is deeply rooted in the rural tradition with a South American twist. They work and live just like their ancestors of 200 years ago. This is a culture that understands how to work in this unique landscape that is dry half the year and flooded the rest of the time. During the season of rains and floods, the horses have to cross water that is chest high and full of caimans. And these cowboys can lasso the caiman or a giant anteater just as easily as a cow.

The Pantaneiros have their own way of riding. They use five layers of wool, sheepskin and leather. Two woven wool saddle pads sit on the horse’s back, topped by a leather tree to which leathers and stirrups are attached. The stirrups are merely heavy round metal rings. Next comes a sheepskin either in a natural color or dyed a bright orange, their favorite color. The final layer is a “baldrana,” a large square piece of leather, similar in weight to a pair of chaps. This makes their long days on horseback easier to tolerate.

And if you look at the Pantaneiros cowboys you can tell if they are married or available by looking at their horse. The flashier and the more “rings” on the bridle, the more it says “I’m available.” And the cowboys wear brightly colored woven belts tied tightly around their waist which holds machetes or handguns. Cow horn cups or “guampas” are attached to the saddles for drinking iced mate. And they tend to wear a distinctive straw hat and always carry both a machete and a knife sharpener. As we would discover later, this proved useful on some of our subsequent forest walks. (See below for more information on the Pantaneiros.)

Morning hike

Day 2, Monday, August 12, 2019

The next morning, we were woken up by the cacophony of the Chachalaca birds.

That was OK because, since I had missed the big hike with the group the previous day, Zapa and Eugenio were taking me on an early private, shortened version of their hike. And it was also OK because later in the day it would be 104 degrees.

We stayed on the property but there was so much to see right there. First there were the toucanets, or aracari. These are small toucans and there were bunches of them. They were all busy eating the fruit on the trees.

- Aracari

- Aracari

- Aracari

- Aracari

- Aracari

- Aracari

There was the beautiful grounds filled with birds and capybaras.

There was also a particularly gorgeous blue and yellow Macaw that just hung out eating seeds and was more than happy to have his/her picture taken.

- Macaw

And there was an old shell of a rhino beetle. And along with the toucanets, there was also a Toco Toucan.

- Toco Toucan

We saw capybaras, caimans, lots and lots of birds, flowers and an owl (which I always thought of as nocturnal, but his eyes were quite open).

- Rufous Kingfihser

- Great Egret

- Pygmy Owl

- black covered donacobius

- black covered donacobius

- black covered donacobius

- Tiger Heron

- Tiger Heron

Caiman

Like the capybara, caimans are everywhere in the Pantanal where there is water, whether a river, a creek, a swamp, a stream or a pond. Caimans are crocodiles’ modest-sized relatives, one of the smallest of western crocodilians, no more than seven feet long and possibly the most abundant in existence today. The caimans found in the Pantanal are the yacare caimans, which are also called the piranha caiman, or southern spectacled caiman (due to the bony ridge between its eyes, which gives the appearance of a pair of spectacles). It is estimated that there are about 10 million caimans in the Pantanal and it seemed like we saw most of them, in all sizes.

The caiman has a smooth, broad, medium length snout. But its teeth are something to behold. It has an average of 74 teeth and some of the teeth on its lower jaw can poke through holes in its upper jaw. This feature makes its teeth more prominent and therefore the caiman has been compared to piranhas and is why it is sometimes called the “piranha caiman.” The scales of the caiman take on the blue-green color of the water it slithers through. Such camouflage, and even the ability to breathe underwater through raised nostrils, sometimes protects it from its biggest predator in the Pantanal, the jaguar.

Another very interesting feature, which Zapa explained to us, is that the caiman, when underwater, can open its mouth but shut off its throat so nothing can get back there if they don’t want it to. This way it can catch fish, then come out of the water to swallow.

When it is hot, the caimans sit with their mouths open to lose heat. They can’t lose heat through their skin. So you often see them just sitting very still with their mouths wide open.

They also have the ability to burrow into the mud for up to three months. This is called estivation (a state of animal dormancy, similar to hibernation, although taking place in the summer rather than the winter; characterized by inactivity and a lowered metabolic rate, that is entered in response to high temperatures and arid conditions).

Heading to Porto Jofre

After my private hike and breakfast, it was time to say good-bye to Eugenio, climb into one of two vans and head on to our next spot.

After my private hike and breakfast, it was time to say good-bye to Eugenio, climb into one of two vans and head on to our next spot.

We drove on the Transpantaneira Highway, the red dirt road, this time counting bridges. We passed lots of Brahma cows and all of them were so skinny. In the dry season, there just isn’t enough grass for them. We passed lots of bright yellow Candelabra trees. The sun was rising in the sky. Birds were everywhere. Sometimes we would see a lone egret. Sometimes we would see whole villages of birds. And villages of termite mounds. There would be a dead tree with a bird perched on the top. We saw white birds, gray birds, yellow, orange, blue, purple. We had a blue sky with a smattering of white clouds. There were flowers on the road in purple, pink, yellow. There weren’t fields of flowers but rather a flowering bush here and there. But mostly it was green with the yellow trees, yellow candelabras and brown earth due to the dryness. It was spectacular.

- Great Egret

- Great Egret

- Great Egret

The bridges

As I mentioned in passing above, there are wooden bridges all along this highway. The number seems to be unclear. Whether 100 or 122 or 126, the wooden bridges by now are old and decrepit, in varying states of disrepair. Some are slowly being replaced with concrete bridges, but most of those haven’t been completed and just end in mid-air. Many people just end up driving around the bridges rather than over them, at least in the dry season. In the wet season that is not an option.

And as we drove along, we kept counting bridges. At least we tried to count them, but of course, we lost track. Karl however kept counting and ended up with a total of 107.

Deer of the Pantanal

We saw different types of deer. There are four types of deer in the Pantanal. And we saw all of them.

Brocket Deer

There are different types of Brocket deer, so these count as two. This one, like many of them, was small and was roaming around the trees. The name, brocket, comes from the French meaning ‘spindle,’ a word for a stag in its second year with unbranched antlers. And they tend to be nocturnal. When threatened by predators (yes, you guessed it, the jaguar), they use their knowledge of their territory to find hiding places in nearby vegetation.

This time we saw a brown brocket deer, the type who tends to be a loner. We saw others throughout the trip.

Pampas Deer

Pampas deer are known to live up to 12 years in the wild but are threatened due to over-hunting and habitat loss. They are light in color and their coat does not change with the seasons. They have white spots above their lips and white patches on their throats. They are on the smaller side, standing about 25 inches. When they run, they lift their short, bushy tail revealing a white patch. Males have small, lightweight antlers that are 3-pronged, Pampas deer do not defend their territory or mates, but do show dominance by keeping their heads up and trying to keep their side forward.

Marsh Deer

That morning we saw a marsh deer with large, forked antlers. And then many others throughout the trip.

The marsh deer are the largest species in South America, reaching a length of 6.5 feet and a height of 4 feet. And they are endangered. They have large ears lined with white hairs. Their skin is tawny brown fur. Their eyes are black with white marks surrounding them. And their legs are long and black, which helps them camouflage in the water. And of course, their biggest predator is the jaguar.

We all climbed out of the vans and took turns peeking at the marsh deer, trying not to spook him. He ignored us, just munching on the leaves. Eventually, he tired of eating and just sauntered off.

Then it was back into the vans and back to counting bridges.

The red dirt road continues

We passed multiple marshes with hundreds of different species of birds as well as more caimans. We saw a bard ant shriek (a striped bird) and egrets, mostly solitary, but now and then in bunches on the trees or marshes. Ruthi called that a hotel of birds. We saw a tiger heron. And we saw so much more. And then we couldn’t help wondering, what else is sleeping or hiding out there that we can’t see?

- Tiger Heron

- Great Egret

- Jabiru

- Great Egret

The rain brings the fish

We stopped on a bridge and all got out to look down at the pool of water filled with caimans. The water was bubbling. Zapa explained that as the heat rises, the oxygen levels fall so the fish blow bubbles to oxygenate the water. However, their vibrations and the bubbles make the fish easier prey for the caimans and birds.

- Great Egret

As the dry season goes on, and the water disappears, the birds and animals move around in the quest for water. The fish lay their eggs in the mud and then die off. After the first rain, the eggs, left by the fish, hatch and suddenly the ponds are full of fish again. The natives believed therefore that it was the first rains which brought the fish.

On the other side of the bridge, the water was filled with birds. An Amazon Kingfisher was sitting on the ledge of the bridge. We saw lots of egrets, a Roseate Spoonbill sitting on a tree, and lots of jabiru.

- Roseate Spoonbill and wood stork

- Roseate Spoonbill and wood stork

- Green kingfisher

Jabiru

The jabiru also gets it own section. The jabiru is a large stork, most common in the Pantanal. In fact, it is the symbol of the Pantanal, where it is called Tuiuiu (pronounced tu yu yu) from the Tupi-Guarani language. The word “jabiru’ means swollen neck. More on this later.

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

The jabiru is the tallest flying bird in South America, standing up to 5 feet, with the third largest wingspan of 7-9 feet (after the albatross and the Andean condor). They are primarily white birds with a black head, a long, black beak and black neck, and with a large red featherless and stretchable pouch at the base of the neck which looks like a red velvet ribbon. When the jabiru is mating, the red turns a vibrant almost neon red. And when they are hot, their black necks become bloated, filled with air to keep cool.

Both parents build their nest out of sticks on very tall trees, and they return to the same nest each year. Thus the nest gets bigger and bigger as more sticks are added. The parents take turns incubating the clutch of two to five white eggs. Although the babies are ready to fly at about 3 months, they often spend around another 3 months in the care of their parents. For this reason, pairs breed only every other year.

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

- Jabiru

When we were in the south, we came upon a marsh that was 6-7 feet deep. There were a number of jabiru fishing. As I mentioned these birds have really long beaks and they repetitively put their beaks into the mud, causing a vibration and stirring things up. They are then able to catch eels, worms, fish, clams, whatever. Some of the longest worms in the world live in the Pantanal. We saw one jabiru catch a few clams and then a worm who was at least 12” long. Many small birds hang out around the jabiru because they stir up so many insects that it is easy for the other birds to feast.

Ruthi and I fell in love with this bird. It was so magnificent and royal looking with its commanding presence. And when it flew, it was incredibly graceful. We saw jabirus everywhere, both in the north and south. We saw them walking and searching for fish. We saw them in their nests. We saw them flying. We saw them alone and in pairs and in groups. And each time, we fell in love with them over and over again.

Anaconda

We continued on our way. Within a few minutes, Chaco, who was in our van, suddenly stopped the car and yelled, “anaconda!” It was crossing the road right in front of us and we all scrambled to get out and take pictures. It was yellow on its stomach and grayish silver on its back with reddish-brownish stripes on its tail and similar colored spots on its body. It was rather gorgeous. It was about 6 feet long. Since I was in the back of the van, I didn’t get out fast enough to take a picture, but luckily David did, and Gary got a video.

Anacondas, or Eunectes, are semi aquatic and are in the boa family. The name Eunectes is derived from the Greek word which means “good swimmer.” But the name anaconda is a word from Sri Lanka. The name likely traveled as Portuguese sailors and colonists moved between Portuguese settlements in Brazil and Asia. Anaconda became a generic word for a large snake.

The anaconda are the biggest snakes in the world often in length, and always in size and power. Life in the water helps support the anaconda’s heavier weight and girth, making the snakes fatter and more muscular than its land-based cousins.

The anaconda eats infrequently, often with intervals of several months. It kills its prey by constriction. The digestion of a single meal can take two weeks or more once the prey has been swallowed. The indigestible bones are eventually regurgitated. It can eat a whole capybara. They have six layers of sharp teeth which are hooked so that if you attempt to back out of its mouth, your flesh will tear. According to the Pantaneiros, if you are bitten, you have to push in slightly further, forcing the anaconda’s mouth to open and then unhook their teeth. Most prey don’t ever get this opportunity as the bite is immediately followed by the snake lifting its victim and maneuvering to coil itself around it, suffocating the pray.

While there are four types of anacondas, only two are found in the Pantanal, the Green and the Yellow Anaconda. Sometimes it is hard to tell the yellow from the green anaconda as the yellow may appear olive green. But their undersides are yellow and the black circular markings on its back are more likely to touch and merge, forming a complicated pattern. The yellow anacondas are smaller than the green species but are more common in the Pantanal. They can grow up to about 14 feet, so the one we saw was rather short.

Later, when we were on the river, we floated by an area of the bank that was full of holes. Every time we passed it, we slowed down and Zapa would carefully look. He was looking for snakes as this is where they nest or burrow. Most of the times we passed the holes were empty. But one morning Cindy spotted an anaconda in one of the anaconda “hotel” holes. It was slithering along the bank amongst the foliage which made it hard to see. Zapa estimated it was about 10 feet long. He then found a second one already curled up in a hole. It was apparently sleeping so we could only see its head, which was huge and bright yellow with black spots. Then we saw a third one all curled up with just part of the middle of the body sticking out. Zapa thought that one was even bigger. He joked that we could now photoshop the tail from the first, the head from the second and the middle from the third to make a complete snake. Zapa said that he went two seasons without ever seeing any but there are now more and more and they are easier to find.

- Look closely at the face. A bit out of focus as the boat was moving.

Yellow-tailed cribo snake

Another time when we passed the holes in the bank we saw a yellow-tailed cribo snake (Drymarchon corais, also called an indigo snake) about 7 feet long, slithering around, sticking its head in and out of holes as it searched for food. As much as I don’t care for snakes, this one too was beautiful. It was a translucent green on the first half of its body and bright yellow on the second half. Zapa said that although very pretty, and although nonvenomous, it is an aggressive constrictor.

Jaguars – whoops, not yet

The ride was bumpy over the uneven but quite flat road. We drove through an 200,000 acre ranch which raises Brahma cows and horses and also helps support the state park.

We stopped briefly at a resort on a riverbank for quick bathroom stop. And there were jaguars. Ok, ok, these were statues too, but we all had fun posing with them. And with the caiman. We also all bought a wonderful pamphlet about the birds of the Pantanal which helped me identify the hundreds we saw.

Hotel Pantanal North Porto Jofre

Four hours after leaving the Araras and crossing the Pantanal, we finally arrived at the Hotel Pantanal North Porto Jofre Lodge. This was once a farm, not a lodge. One day, a fisherman, who had caught many, many fish, stopped by and asked if he could spend the night. When he left the next morning and returned to his village, he shared the news of this river full of fish, of the bounty of the Pantanal and of the farm that let him spend the night. More and more fisherman started coming and the farm turned into a fishing lodge. And then the fisherman started posting photos of jaguars they had seen and slowly, slowly, tourists starting coming just to see the jaguars. And thus the Hotel Pantanal North Porto Jofre evolved. Now it is filled with both tourists and fishermen.

And the name Porto Jofre? The name of the farm was Jofre. When the Transpantaneira Highway was built and ended here at the Cuiaba River, this became the port for transferring cattle and food. Thus, the name became Porto Jofre.

The lodge has 36 rooms, all of which seem to have three beds (two single and one double). Each bed had the towels shaped into a heart. Each room has a refrigerator and bottled water. All are air-conditioned, which when we were there was quite necessary. There was no closet, but there was a coat rack and plenty of space to put our packing cubes (is there any other way to travel?!). The only problem we had was we could not figure out how the hot water worked and ended up with cool showers. I’m sure there is some trick as everyone else had hot water. And although they came to show us, we still could not get a hot shower. There were also lounge chairs outside each room if you wanted to sit and relax and watch the birds. (Or dry your laundry on them).

- Bottled water

The lodge has a swimming pool and is surrounding by the river on one side and a large lagoon on the other. The lagoon is crossed by a long wooden bridge, but we were warned not to get off on the other side. Jaguars or other animals might be lurking there. There was a small chapel as well, right by the landing strip, to welcome people when they arrive.

There is a fairly large dining hall with two rooms. Food is served buffet style. The food is all locally grown or caught. There were multiple choices for lunch and dinner, including a fish dish, a meat dish and a vegetarian dish.

The lodge has its own vegetable garden and on our last morning we got a behind-the-scenes tour of their organic garden and the operations center. Their greens were gorgeous and there was a row of Paku and catfish hanging to dry, which is apparently a delicacy for the Brazilians.

The grounds are green with lots of lawn space. And of course, there are birds everywhere (real and not-so-real). Hyacinth macaws were almost in every tree.

- Black vulture

- Flying macaws

- Egret

- Clay colored thrush

- Savanna hawk

- Chaco Chachalaca

And the owner’s sister feeds toucans every morning and every afternoon which gave us a chance to photograph them at close range.

- Toto Toucan

In the morning, horses came to graze.

The lodge has its own fleet of boats which made it very convenient as we explored the Pantanal, and which were beautiful when all lit up at night. The lodge also has its own landing strip (a long stretch of grass) which we got to use on our last morning as we flew out.

Lily Pads

Close to the shore by the bridge were large lily pads, sometimes called Queen Victoria’s lily pads (Victoria Amazonica), perhaps 4 or 5 feet in diameter (although they can grow up to 9 feet). Whenever I had seen pictures of the Pantanal, this is what I saw. But this was the only place we saw them. They were beautiful, in different shades of green with white and purple lilies blooming. I saw them described as looking like big green dinner plates on a blue tablecloth.

And sometimes, the caiman came to visit here too.

Time to hit the water

After settling in and having lunch, it was time to head to the water. Finally, finally we might have the chance to see jaguars.

We all trudged down to the water, outfitted with neck buffs (the most important item to take with you on this trip) and hats and settled into our fast 250 hp skiff. Chaco was with us as well as our helmsman (boat driver), Gonzelino. And so we headed upstream on the Cuiaba River, the three of them always on the lookout.

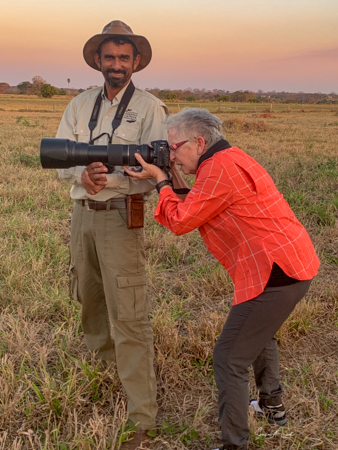

- Chaco

- Zapa

Rivers of the Pantanal

The Cuiaba River divides the north and south Pantanal and goes 2000 miles, all the way down to Buenos Aires. We went upstream until it met at a fork with the Piquiri River, a tributary of the Paraná River. The fork represents the beginning of the Pantanal Matogrossense National Park (see below). The water in the Piquiri comes from the mountains so it is cleaner than the Cuiaba which is brownish due to lots of silt. The Piquiri is also the dividing line between two states, Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul.

At different times we passed the Black Creek and the Three Brothers river (Tres Hermanos). Creeks have ends and are fed by marshes. Caimans love creeks because there are lots of fish and no current. We also saw lots of capybaras. The caimans are afraid of the capybara and when the capybara move towards them, they plop back into the water. And of course, there are always tons of birds.

Pantanal Matogrossense National Park

The Pantanal Matogrossense National Park is some of the only land not privately owned by ranchers and farmers. It has been labeled the “Wetland of International Importance,” and covers both the states of Mato Grosso (where we now were) and Mato Grosso do Sul (where we would be going). The park is a protected area, whose mission it is to preserve the natural ecosystem of the area, protecting the beauty and enabling research, environmental education and tourism. The park itself is about 335,000 acres, and much of it is water.

Having said that, the cattle farms still use the rivers to transport their cattle.

Having said that, the cattle farms still use the rivers to transport their cattle.

Tiger catfish

Tiger catfish, called Pintado, are very common here and are a favorite delicacy. They are very different from the catfish we find in the US as these are not ground  feeders. These, also called sorubim, have an elegant pattern of hieroglyphic black markings on a silver-gray background. To catch these fish, you need a license and you are only allowed to catch 5 kilos plus 1 fish. The locals, when fishing for this fish, are not allowed to use nets. Rather they set up poles with bait and leave them overnight to catch the catfish. Since these fish are so expensive, they check their poles at midnight and again early in the morning. We saw the poles in lots of spots on the river, and we were served some variation of this catfish every night.

feeders. These, also called sorubim, have an elegant pattern of hieroglyphic black markings on a silver-gray background. To catch these fish, you need a license and you are only allowed to catch 5 kilos plus 1 fish. The locals, when fishing for this fish, are not allowed to use nets. Rather they set up poles with bait and leave them overnight to catch the catfish. Since these fish are so expensive, they check their poles at midnight and again early in the morning. We saw the poles in lots of spots on the river, and we were served some variation of this catfish every night.

Jaguars – for real this time

As I mentioned above, we all climbed into our boat and headed upstream. We raced across the sparkling water under the brilliantly blue sky with the wind in our faces. Birds were flying everywhere and perching on the very tops of trees. Everywhere we looked there was more and more beauty. And for quite a while, we were the only boat. We passed a few house boats that are hotels, but no other boats racing through the water.

In just a few minutes we saw our first jaguar. He was sleeping but as we watched, he sat up and posed for us. He stood up so we could see his full grandeur. He walked a bit and then went back to sleep. The show was just for us.

And Zapa did his happy dance!

Later in the day, each time we passed this area, other boats were waiting (once someone spots a jaguar, they radio the other boats). But for them, he just slept.

Jaguars used to be rare here. When Zapa first started guiding, about 15 years ago, it took 7 months before he caught a glimpse of one. Then another 11 months before he saw another. At the end of the year all the guides would have a jaguar party and recount how many they each had seen. You had to buy a case of beer for each one you saw. Then the farmers got together and created an area where the jaguars would be safe. So they multiplied. 70% of the jaguar’s diet is caiman and there are over 10,000 caiman for the jaguars to feast on. Now it is estimated that there are 60 jaguars in the park.

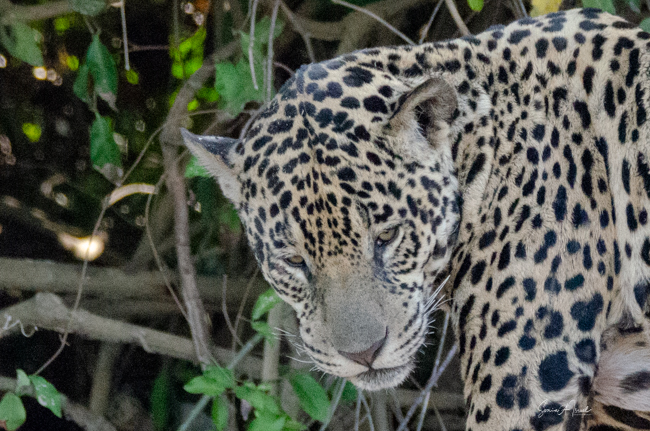

The name jaguar comes from the Tupi-Guarani word yaguar, which means “he who kills with one leap.” They are the symbol of wildness and prominent in ancient religion, mythology and art. The Maya believed the jaguar was the God of the Underworld and helped the sun travel under the Earth at night, ensuring it would rise in the morning. The Aztecs worshiped the jaguars and were the guardians of their sacred temples.

Jaguars are the third largest cats behind tigers and lions, and the jaguars in the Pantanal are the largest in the world, occasionally exceeding 300 pounds and 7 feet in length. Their heads and shoulders are massive, and their legs are relatively short and thick. They are both adept climbers and swimmers, making them versatile hunters. They are at home in trees, on the ground, and in water. In the Pantanal, they hunt caimans by jumping into the water and dragging them back out and they hunt capybaras either on land or in the water. They have been known to kill cows as well. Relative to body size, jaguars have the strongest bite of all the cats, with a crushing power of up to 1,500 pounds of force which allows them to pierce the skull of their prey and even crush bone to access the marrow.

The jaguar is nocturnal, spending most daylight hours snoozing in the sun. The males will hunt at night. They mark an area of about 65 square miles and spend the nights stalking other animals. The younger males and females tend to hunt in the day, in order to stay out of the way of the males.

Here are some fun facts which I got from the Jaguar ID Project website (see below for more info about this project):

- Jaguars are one of the four roaring cats. The roaring is a proclaiming of their territory or bringing together of the two sexes

- Jaguars are one of the few large cats that have melanistic individuals; meaning there is no such species known as the “Black Panther”, it is just a jaguar or leopard with melanism.

- Jaguars are aquatic cats and many rely on aquatic prey as their main food source

- Jaguars actually have 5 toes, but only four leave tracks, keeping the most developed hunting claw off the ground

- Jaguars can eat 8 to 10lb of meat per day

- Jaguars have been known to be nocturnal, but studies show they are often active during the day with peaks around dawn and dust.

Jaguars vs leopards

So how do you tell a jaguar from a leopard? While jaguars look similar to leopards, the jaguar has a much stockier build with shorter legs, and the “rosettes” on the coat of a jaguar have spots inside the rings, while leopards do not. In addition, jaguars are only found in the Americas while leopards are found in Africa and Asia.

…And more jaguars

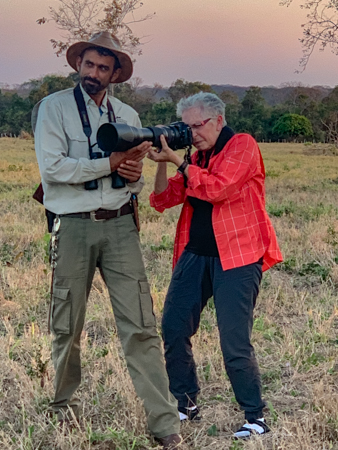

We continued upstream. And there, a second jaguar. This one was much fatter and was surrounded by boats. There were some photographers with very, very large lenses.

But this jaguar just slept and slept. We anchored and watched for a while. He would lift his head. We’d get excited. Then he would put it back down and go back to sleep. Once in a whi le his tail would twitch. He would swipe at a fly with his huge paw. But sleep continued.

le his tail would twitch. He would swipe at a fly with his huge paw. But sleep continued.

So we pulled up anchor and kept going. And on the way back to the lodge, right as the sun was beginning to set, we saw a third jaguar.

This one was sitting on the beach and just watching a family of about 10 capybaras. We knew he was thinking, “dinner.” And we couldn’t help but root for the capybaras to get away. There were two large capybaras, each looking in a different direction, as they are apt to do. And we couldn’t understand why they just sat there. The jaguar got up slowly, and then stealthy starting walking towards them. All of a sudden, we heard a bark and a splash as all the capybaras jumped into the water to get away. Finally! Zapa said the jaguar must be young and inexperienced to have let the capybaras get away. Please see the capybara section above for the videos.

Jaguars lose some color as get older but ours were all young.

So three jaguars. And that was just the first afternoon.

The Giant River Otter

After seeing our first jaguar, we pulled up anchor and moved again, still heading upstream on the Carrizo Creek. Suddenly our boat pilot, Gonzelino stopped. We saw a head bop out of the water. The giant otter.

And then right before our eyes, he climbed out onto the bank where he was building a den.

Dens are built by all members of the family. They clear a living space for their clan, as they are monogamous and have litters of about 5 cubs. But the different generations of offspring live with them, so you could have as many as 12 otters living together. They were once endangered, but no longer.

The den might be as large as 540 square feet but surrounded by vegetation so you can’t actually see it from the river. They clear the area by trampling the surface grasses, they collect tree limbs and leaves and then embed those into the trampled mud. They construct large burrows under fallen logs. And finally, they mark the territory with a scent from their anal glands. And if that isn’t enough, they leave dead fish, urine and poop all around.

So yes, the smell hit us. You can always smell an otter’s den. Putrid.

The otter then went back into the water, swimming so incredibly fast. We would watch him submerge in one spot and seconds later he was a football field away. They swim with an up and down motion just like porpoises. And when we would catch up, he would lift his head and bar his teeth. They are not cute. They are mean, ferocious, and frankly have a face only a giant otter mother could love. In fact, they are so nasty, they are also called water wolves or water jaguars.

We went on and suddenly there was a whole family of Giant Otters. Five of them. Parents and kids. They too were swimming through the water hyacinths where they look for fish. We followed them as their heads bobbed in and out of the water. One caught a fish and swam away to be alone so as not to share. He (she?) looked like a little person, holding the fish with his front feet/paws/hands and eating it like corn on the cob.

They all swam some more and then came out of the water by their den (and yes we could smell it). The parents watched as the cubs frolicked in the water. At one point the 3 cubs swam right towards our boat, teeth barred. But at the last minute they veered off. Must have realized that big jaguar (i.e., our boat painted with a picture of a jaguar) was no match for them.

And the first day ends

As we made our way back around sunset, Zapa passed out bug glasses as we got bombarded by flying insects. We pulled our neck buffs up over our heads and faces. But the wind felt great, and the sun was setting and the sky turned beautiful colors. The moon was full. And we were so happy.

Neck Buffs and Fleece Jackets

Day 3, Tuesday, August 13, 2019

Our morning started early. We made our way down to the water at 630am, just as the sun was rising. Everything was covered in a red glow. It was magnificent.

- Hyacinth macaws

We climbed into our boat and settled in. Neck buffs were pulled up and fleece jackets, hats and gloves were on against the morning chill. We even brought blankets to wrap up in. The boat took off, heading upstream again, and all we could hear was the rush of the waves as the boat sliced through the water. The sound of the wind in my ears. Now and then the cry or song of a bird. The quiet. Totally peaceful.

There were fewer birds out because it was so cold. But as the sun rose and it warmed up, the birds came out flying everywhere.For a while, all we saw were capybaras and birds. The capybaras were on a small plot of sand and it seemed to be a whole family of parents, a teenager and three little ones. Zapa estimated they were less than a week old. They totally ignored us, but we had fun watching them.

The birds were beautiful, as they always are. They were everywhere and they were singing their hearts out. Flying in formation. Perched on trees. In the water. Birds, birds, birds,

- Cocoi heron

- Rufescent tiger-heron

- black capped donacobius

- neotropical cormorant

- Cocoi heron

- Hyacinth macaws

And of course, caimans. Everywhere.

We veered off the main river onto the Three Brothers River and then into a small creek. There were beautiful red trees along the banks called Brazilian ant trees because they are millions of ants on them. So, beautiful, but do not touch! Zapa also cautioned us not to touch the long grass along the marsh, the razor grass since, as the name suggests, it is very sharp.

Howler Monkeys

We kept going up the creek. We suddenly heard a loud howl. Yes, a howler monkey, specifically a Paraguayan howler monkey, sitting on top of a candelabra tree. They really do howl. In fact, they protect their turf with their roars. She was hard to find as she was quite camouflaged. Zapa said there was a family around but we didn’t see the others. They apparently don’t move around much and mostly sit up in trees and eat leaves.

How did we know it was a she? The females are brown and the males are black and larger.

The howler is the largest of the Pantanal monkeys, weighing as much as 10 pounds. They aren’t particularly aggressive but their howls sound like they are. The male starts each day with a call that sounds like the roar of a lion. In the evening, at dusk, the males get together and sing as if in a chorus. This gets particularly loud if any trespassers get to close. And that sound carries over a mile, which is why we could hear it so clearly. We often heard the howls no matter where on the water we were.

How do they “sing” so loudly? They have a very large larynx and throats which inflate into resonating balloons and are often compared to Pavarotti-like vocal abilities.

Howlers are similar to reptiles in that they have to warm up before they start eating. Then mainly eat leaves and figs. Hawks and eagles are their predators.

Later in the trip we saw another family in the trees, howling away.

At different parts of the trip, we also saw other monkeys.

Green Iguana

At another point Gonzelino suddenly stopped the boat and Zapa pointed out an iguana. This was a green iguana, which is a large lizard found in the Pantanal. It was just sunning on the tree and with the sunrays on it looked iridescent. The next day we saw a second one. I still don’t know how anyone can spot them as they blend right into their surroundings.

Bathroom?

We had been cruising for a few hours now and it was time for a bathroom break. Of course there are no bathrooms out there. So Zapa found a place we could pull the boat up and climb up the bank. He went first, clapping his hands to scare away anything that might be there and making sure it was safe, that is, no animals we would not want to run into. It was sure full of termite mounds, but luckily no animals. Once he felt it was safe, the women all climbed up the bank, with our toilet paper and plastic bags and we each found a spot to do our business. The men had it easy; they just went by the boat.

Caiman Alley

We got back into the boat and went up another river called the Cairna river, unofficially called “Caiman alley.” There were huge caimans there because are so many catfish living here. This river also connects with the Cuiaba river. There are thousands of interconnected and intertwined rivers/creeks and easy to get lost. Our driver has been a boat driver in this area for over five years and knew exactly where we should be when.

And then the radio call came

And then the radio call came. Jaguar. We took off at neck breaking speed. Hugging the corners. Water spraying. On the hunt. Anticipation great- would the jaguar still be there. We raced down one river and onto another.

And then the radio call came. Jaguar. We took off at neck breaking speed. Hugging the corners. Water spraying. On the hunt. Anticipation great- would the jaguar still be there. We raced down one river and onto another.

And then we saw all the boats. The cameras were all pointed in the same direction.

the boats. The cameras were all pointed in the same direction.

And then we saw him. One beautiful jaguar walking through the tall grass. But wait. Right behind him was a second one. Brothers.

The Tale of Two Brothers

All the jaguars previously identified are named. Later we learned that the first brother we saw was Borro (also called The Brother Arara, Tore or Os Imaos). He is the “son” of Kyra and was first seen in 2017, making him about 2-3 years old. Borro walked through the tall grass, stopping now and then to examine his surroundings, and us. They are so used to boats that we don’t bother them. And a few feet behind him came his brother, Ando (also called The Brother, Os Imaos, Kim, Inho). You might be wondering how I could tell them apart? Borro has a marking above his nose that is shaped like a horseshoe. Ando has one more like an angled line.

- Boro

- Ando

Ando continued to follow Borro. In anticipation of them reaching the beach up ahead, we moved our boat to get a good vantage point.

And sure enough, after many minutes, Borro broke through the tall grass onto the beach. He paced back and forth. He sat down. He yawned. And then he paced some more. He went to the other side of the beach and walked into the water, and then back out again. Suddenly he called out. Zapa translated for us. Borro was calling for his brother, Ando. Essentially, he was saying, “Ando! Where are you?”

Ando, in the meantime, had spotted a capybara and decided it was time for lunch. He jumped into the water, but the capybara was faster this time and got away. Ando slowly swam back to the shore, climbed up and made his way through the grasses to the beach. When he emerged, his wet fur was much darker.

Borro walked over to him and they started rubbing against each other as if they were hugging. Brothers.

We watched for some more minutes until the two brothers walked back to the tall grass and disappeared from sight.

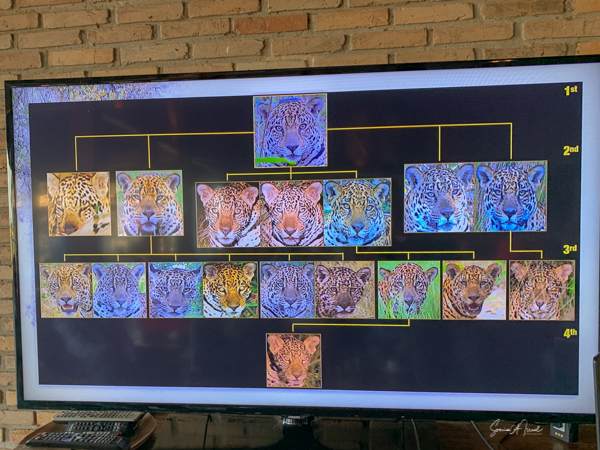

How Jaguars are Identified

Abbie Martin runs The Jaguar Identification Project, a non-profit which uses citizen-science to build a cohesive database on individual jaguars in the northern Pantanal region [www.jaguarsidproject.com; info@jaguaridproject.com] They have been following individual jaguars and documenting their behaviors since the early 2000s. Each jaguar is identified by its spot pattern, which is like a fingerprint. Most of the photos are supplied by tourists and each jaguar is cataloged in the Jaguar Guide which lists individual behaviors, lineages and relationships, and home ranges and movement. The guide is available as a pdf for $10.00.

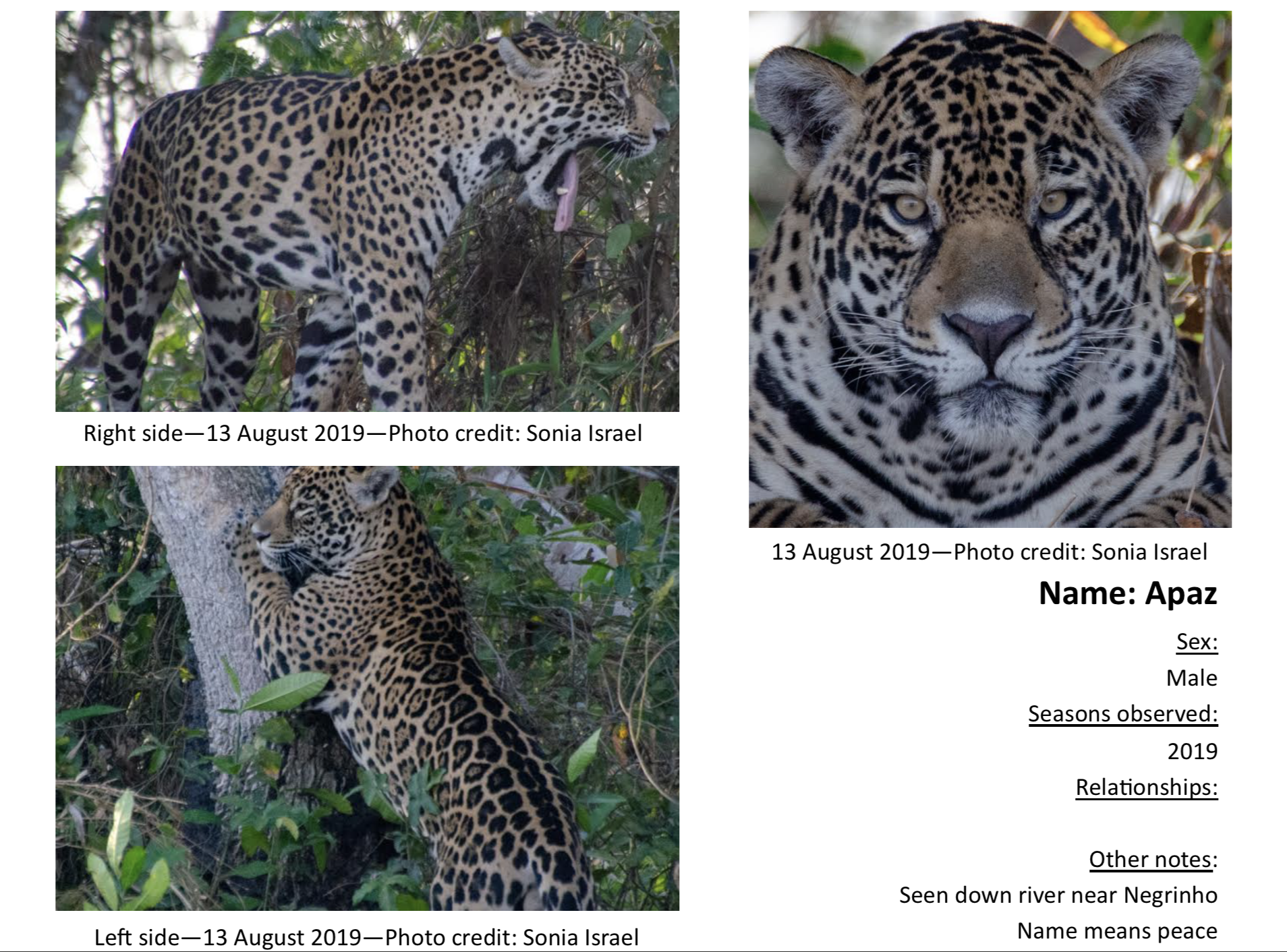

Apaz

After we left the Brothers, it was back to the lodge for lunch and a break from the mid-day heat. It was about 96 degrees. And then at about 3:00 pm, we were off again. Zapa decided to head downstream on the Cuiaba River instead of the usual upstream to the national park. He warned us that we night not see any jaguars. Very few people head downstream as one of the goals of these trips is to see jaguars and fewer have been seen downstream and those that are there seen, are not as habituated to boats and are more wary of us. But Zapa, our fearless leader, thought the beauty and the serenity of that area would be worth it. So off we went into the Rio Negronho Creek.

And before we knew it, near the Boca Brava channel, on the right bank, we saw a jaguar (our 6th in less than 24 hours and over 102 miles of river). Zapa thought he was a young male, probably about three years old. He had not mated yet as his face was not yet scarred (see below for an explanation of this). He was sitting by a tree on the riverbank, overlooking a group of caimans below. We assumed he was waiting to catch his dinner. We watched for over an hour, but he never pounced. He sat. He watched. He yawned (showing us his very, very long tongue). Eventually he got up, walked over to a tree, put up his front paws and marked his territory, at which point all the caimans jumped under water with a big splash. And then he walked off and we continued on our “cruise.”

Later that evening, back in our lodge at the Pantanal Norte, we ran into Abbie Martin of the Jaguar Identification Project I just described above. When she heard we saw a jaguar downstream, she asked if I had any pictures. Did I have pictures? Do you know me?! I emailed her some photos and received this response:

“Congratulations you got yourself a new jaguar!! So we do have some naming guidelines. We ask you to choose a name that relates to this individual, the way you think it looks, your experience with it or its behavior. We do not accept names like Kitty or Spot or a name of a ex boyfriend..etc.. you get the point. If the word you choose is English I will translate it into Tupi-Guarini the indigenous language of the region.”

And so we got to name the jaguar! I decided that although I took the pictures, I was not the first to see it. And it would be more meaningful to Zapa to name a jaguar than to me. Zapa suggested we name him as a group. He came up with “Dear Friend.” This was so fitting for so many reasons. The first is that Zapa always addressed us as “dear friends.” The second is that we felt that “our” jaguar was indeed our dear friend. So now we waited to hear what the Tupi-Guarini version would be.

I emailed the name to Abbie and a day later got this response:

“Thank you for getting back to me. Sorry but ’Dear Friend’ is a very strange jaguar name even if it’s translated into Portuguese. Can I suggest you name him Zapa? What do you think?”

Well, we all loved the idea of naming him ‘Zapa.” But Zapa was not wild about that idea. So it was back to the drawing board. At this point we were all heading home and continued our deliberations via email. Johanne came up with the idea of naming him Apaz. First, that is Zapa backwards. Second, it Portuguese it means “peace.” We all loved that idea, as did Abbie.

So our jaguar is named Apaz. Here is the page from the ID book.

White caps

On the way back to our lodge, heading back upstream, the wind picked up. The boat was speeding, There were white caps on the water. We all moved to the back of the boat to so the front could rise out of the water. We huddled close, dressed in our warm jackets, neck buffs pulled up over our heads and faces, with only our eyes peeking out (and even those had our bug glasses over them), blankets covering us. Hard to believe that earlier it was 96 degrees.

And so you can “feel”the wind, listen to this video.

The sun was setting, the moon was rising, it was getting dark. But Zapa never gave up looking for more things to show us.

Another beautiful morning

Day 4, Wednesday, August 14, 2019

This was an early morning again and it was cold. We got to the boat and wrapped up in our fleece jackets, gloves, hats and blankets. But our hearts were warmed by the beautiful sunrise.

We headed upstream again, back into state park. We passed the bank with all the  holes in it and searched for anaconda, but no luck this morning. And then we saw boats. At this point we knew that meant jaguar, our seventh. (Zapa told us that the group who came in July never saw even one jaguar). This one was sound asleep. The sun shone on her. The morning light was perfect. We hoped she might stand up, stretch and pose before going back to sleep. No such luck. After about 20 minutes we were on our way again, cruising up the river in search of more wonders. The morning wind had died down and the Cuiaba River was very calm.

holes in it and searched for anaconda, but no luck this morning. And then we saw boats. At this point we knew that meant jaguar, our seventh. (Zapa told us that the group who came in July never saw even one jaguar). This one was sound asleep. The sun shone on her. The morning light was perfect. We hoped she might stand up, stretch and pose before going back to sleep. No such luck. After about 20 minutes we were on our way again, cruising up the river in search of more wonders. The morning wind had died down and the Cuiaba River was very calm.

We ran into a family of howler monkeys (see above for more info on howler monkeys). There were four high up in the tree and one female on a branch further down. We floated for quite a while watching them and listening to them.

Mother and cub – numbers 8 and 9

We started up the river again and there were more anchored boats. Yes, jaguars. It was a mother, Tina and her 1-year old cub Matthew. The mother was sound asleep as she is well habituated to all the boats. We could just make out her nose through the foliage. The cub was just learning about boats. He would raise his head, see mom wasn’t worried, and go back to sleep. And thus he was also slowly getting habituated. And that was number 8 and 9.

Number 10 and 11?

We came upon a dead Brahma cow carcass in the water along the shore. As we arrived, the two brothers were just walking away into thick vines and brush. Some of us just caught a glimpse of them, but others in our boat did not.

We came upon a dead Brahma cow carcass in the water along the shore. As we arrived, the two brothers were just walking away into thick vines and brush. Some of us just caught a glimpse of them, but others in our boat did not.

We waited for almost an hour, wishing for either these jaguars to return or vultures to come down, as Zapa said if the vultures came, it was likely the jaguars would return to defend their carcass. But the vultures just flew and watched, but never came close to the carcass. And the jaguars did not return. So we pulled up anchor and left.

- Chaco

The big discussion in our boat was, do we count the same jaguars twice, which would make these 10 and 11, or do we count each only once. I voted for only once. So no 10 and 11….yet.

Gonzelino took us back into Caiman alley. It seemed like the caimans were twice the size of yesterday. Although we did not see them here, the brothers mostly live around here. And why not? It would be the equivalent of a caiman buffet.

Birds, birds and more birds

The river was full of birds today. We saw a Great Heron catch and eat a fish.

- Great Egret with fish

- Great Egret with fish

- Great Egret with fish

Watching all these beautiful birds day after day made me realize that I never understood what color really is. (For a full list of all out birds and more pictures, see below.)

- Red-legged Seriema

- Red-legged Seriema

- Tiger Heron

- Great Egrets

- Great Egrets

- Great Egrets

- Great Egret

- parrot

- Southern Caracara

- Squirrel cuckoo

Our last afternoon on the river

Unfortunately, our time in the Northern Pantanal was coming to an end. Our last river cruise was this afternoon. We went onto the Piquiri River, for the first time and then back to a different part of Black Creek. Although the Piquirri is supposedly more pure as it comes down from the mountains, it looked pretty brown and silty.

We stopped to photograph a beach with a jaguar on it…..

Another boat of tourists thought they saw a jaguar. The birds were going nuts but unfortunately, despite waiting about 40 minutes, none of us could see it. So we continued up the river.

Inside bends. Outside bends

We had gone up and down many of the rivers and creeks at this point. Using his elbow, Zapa explained that at the bends of the rivers, the “Inside bend” will have a “beach’ while the outside bend will have significant tree/vine growth. This is a function of the currents: the push of the rivers on the outside banks erode the bank while new land and eventual growth occurs on the inside bank. The erosion also explained why we saw so many tree roots along the river banks.

We had gone up and down many of the rivers and creeks at this point. Using his elbow, Zapa explained that at the bends of the rivers, the “Inside bend” will have a “beach’ while the outside bend will have significant tree/vine growth. This is a function of the currents: the push of the rivers on the outside banks erode the bank while new land and eventual growth occurs on the inside bank. The erosion also explained why we saw so many tree roots along the river banks.

Wine at sunset

We anchored in Black Creek just before sunset. Zapa and Chaco brought out wine glasses and bottles of Sauvignon Blanc (I’m pretty sure cause they knew it was my favorite). As we watched a gorgeous sunset on one side and moon rise on the other, we toasted to a wonderful trip so far!

Final thoughts on the Northern Pantanal

The whole time on the water was so relaxing and soothing. The wind in my face. Warm, although we all brought our fleece. Sun rising reflecting on water. At times the sun peeking through the trees. And the smell of freshness. River water. Morning.

There are songs written about this, called Relva. That is the smell of the forest. The smell of fresh air

Good bye to the North; Hello to the South

Day 5, Thursday, August 15, 2019

This was our last morning at Pantanal North Porto Jofre and we were sad to go. Our flight wasn’t until 9:00am so we had a lazy morning. I walked around the grounds with my camera. Near the bridge there was a family of Southern screamers – two adults with their chicks. I watched them, and listened to them, for quite a while. They were just being a family.

- Southern Screamer family

Bird’s Eye View of the Pantanal

The Pantanal North Porto Jofre lodge has its own landing strip, a large grassy area similar to the landing strips we experienced in Africa on safari. There were two small planes waiting for us. We said farewell to our local guide, Chaco, who was off to guide a group of German tourists and “boarded” our plane.

Zapa assigned us to the planes and the pilot told us which seat we were to take, based on weight and length of legs. Debra and I were in the back of the Cessna 206, a five-seater, along with David, Gary and Carol. Ruthi and the rest of the crew were in a Cessna 208 B grand caravan which is a 9-seater.

We rolled down the “runway” and took off ahead of the other plane. Since we were smaller, we were slower, but also could fly lower for better views. The caravan flew higher and faster, which made it harder from them to get pictures. It took them about 65 minutes to transverse the 200 miles, and us about another 15 minutes, a trip that Zapa said would take over 19 hours by car.

And the view from up above was spectacular. We first flew over the lodge and could see the river and the grounds and the bridge over the lagoon.

Then we flew over a canopy of blooming candelabra trees, which looked like a thick yellow carpet. We passed our river, the wonderful river we had just spent 3 days on. The ground was green, but in a dry sort of way. We could see lots of dry riverbeds and could only imagine the sight during the wet season.

At one point, since our plane was so small, the pilot lowered the plane and we felt like we were getting ready to skim the treetops. The land alternated between barren brown, dry land and forests of green trees. There were no real roads. We could really get a sense of the huge expanse that the Pantanal covers. We could see how the water holes were drying up during this normally dry season. And all those areas with no trees would soon be underwater when the wet season arrived. Zapa said that in the wet months, one cannot see the ground at all.

And here the ground had large puddles (not really lakes) with dead trees creating sculptures designed by Mother Nature. She is the most magnificent artist of all.

After a bit we rose higher again for more of a bird’s eye view. There was a winding river now and then. A ranch or two. But no roads. No cars. Untouched.

I imagined what was living down there. Which birds were hiding in those trees? Which mammals called this home? Yes, Zapa would tell us the names. But I tried to imagine the actual creatures moving around under the canopy. Each trying to survive another day.

And suddenly the color changed from dark green to light green. The terrain changed. It wasn’t gradual. It was like someone had drawn a straight line with a ruler. We had crossed over some sort of border. We started descending, getting closer and closer to the treetops. We flew over fields of white Brahma cows and ranches. Welcome to the Southern Pantanal.

The Southern Pantanal

The Southern Pantanal is quite different than the Northern Pantanal. Yes, there are still myriads of colorful birds, caimans, howler monkeys, jaguars, giant anteaters, tapirs, ocelot, etc etc. But down here is the land is made up of mostly of cattle farms. And here we would be touring in a safari vehicle, not a boat racing through the rivers. Having said that, the Southern Pantanal actually floods more than the North. This means that at certain times of the year there is an explosion of aquatic vegetation.