April 17-18, 2018, Tuesday and Wednesday

The Skeleton Coast

After breakfast today we hit the road heading north to the Skeleton Coast. We were driving in Dorob National Park, a protected area in this region of Erongo. It is 990 miles long and covers 41,500 square miles, from the Kuiseb Delta, just south of Walvis Bay, to the Ugab River, where we were heading. There are about 75 species of birds that live here and it feels like we saw many of them.

The road was paved, but grooved and rough, at least for a while. We were surrounded on both sides by sand. Sand, sand and more sand. And to our left, on the west side, on the other side of the sand, was the Atlantic Ocean. Other than that, there was not much to see.

Did I say there wasn’t much to see? There was. We passed a salt mine with mountains of what looked like snow. We saw birds of all sorts. We saw small green bushes come and go and the sand. We saw sand dunes suddenly arise from nowhere and just a quickly, disappear back into the flats. We passed small groups of houses, not even as large as a village, where fishermen or those working in the mines lived. And their homes were all big and colorful, breaking up the white of the sand. Those colorful houses were built by the Germans which is why they were all so large. Then they were bought by the Uranium mines, which are owned by an Australian company, for their workers.

We saw a desalination unit being built (with help from South Africa) and long pipes being laid in the sand to bring the water. Between the drought and the amount of  water used in the mines, it makes perfect sense to take water from the ocean and desalinate it. This might also help with the drinking water. Everywhere we went we were told we could brush our teeth with the tap water, but do not drink it. The water from here will go primarily to Walvis Bay and to Swakopmund.

water used in the mines, it makes perfect sense to take water from the ocean and desalinate it. This might also help with the drinking water. Everywhere we went we were told we could brush our teeth with the tap water, but do not drink it. The water from here will go primarily to Walvis Bay and to Swakopmund.

We saw almost no other cars, and yet, they are building another road parallel to the one we were on. Charles said it was for all the trucks. But I didn’t see any trucks.

Every few miles I would see a sign with a name and a picture of a man holding a fish. This is a prime ocean fishing area. The fishermen buy a permit for N$15 and  are assigned a specific spot to fish. Thus the names on the signs.

are assigned a specific spot to fish. Thus the names on the signs.

We passed huge lichen fields. These are all protected, with fences around them to keep people from walking or driving over them. This is one of the few protected areas in Namibia. There are about 120 species many of which grow only here. And why are lichen important? Because they enable algae to live and provide a means to convert carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, through photosynthesis, into oxygen.

The Zeila

We drove and we drove. In the distance we could see a shipwreck. We drove the car onto the sand and parked. We climbed out and walked through the sand to see the shipwrecked Zeila, which was shipwrecked in 2009. We stood there watching the birds swarm the ship. It is now a good place for nests. I tried to imagine what the men must have felt or thought. Here they were stranded in a desert. No food. No water. No way to survive. And now the remains of the shop stand as a monument.

The Zeila was just one of many, many ships that were shipwrecked here. I already wrote about the Eduard Bohlen, a 2,272 tom German passenger and cargo ship that was on route from Swakopmund to Table Bay. In September of 1909, it lost its way in the thick fog and ran aground at Conception Bay. Because of the change in the ocean tides, it now sits inland, and is partially buried in the sand. We saw it from the plane on our scenic flight (please see the post on Sossusvlei).

So why do many shipwrecks? Well, this is the Skeleton Coast. Due to strong cross-currents, heavy swells and dense fogs caused by the ice-cold fast-flowing current from Antarctica, this is one of the most treacherous coastlines in the world. There are also rocky reefs and sand dunes that stretch into the sea which spell disaster for any vessel that gets caught up in the gale-force winds and all-enveloping sea fogs which reduce visibility to nothing.

But it is not only the ships that give this area its name. There are stories of the sailors from these ships, walking through the desert in search of food and water and their many bones found years later. There are also bones form the whale and seal that ran aground, or that floating onto the sand as a result of whaling.

On the way back to the car, we were accosted by men trying to sell us rock and crystals. Seemed so strange to see people hocking their wares literally in the middle of nowhere.

Hentis Bay

It was back on the road again, this time as far as Henties Bay, a small “resort” town full of nice houses.

This was a good spot for a rest stop. We paid to use the facilities  at a gas station. We had to pay to use it and the toilet paper was already cut up for us.

at a gas station. We had to pay to use it and the toilet paper was already cut up for us.

The Namibian Flag

There was a small gift shop with the Namibian flag hanging outside. Charles held it out and explained that the green was for the land, the white for peace, yellow for the sun, blue for the sky and red – red was for the bloodshed.

There is also an African Union flag with has the green, white and yellow for the same reasons.

Heading North Some More

And then we hit the road again. We continued north. There were riverbeds that were all dry and easy to drive over. The desert was vast. The terrain kept changing. Suddenly there would be huge patches of what looked like snow. It was salt.

Low mountains appeared on the east. There was no longer sand beneath us. The road and the area around us looked like it now had little black rocks in it, like gravel. In fact these were washed down from those low black mountains. And the road was covered in red dirt. We passed one mine after another. But none seemed to be operating. The roads were desolate. There were no birds except for one lost gull. Desolate. Isolated. Bleak. Stark. Yet beautiful.

We drove and drove some more. The road turned back to sand. And then, along the side of the road, we started seeing little makeshift tables with quartz blocks on them. For sale. But there was no one around. IT was a bit bizarre. Table after table. Sometimes just an upside-down barrel. Full of quartz. Perhaps if we stopped the care and got out someone would appear from nowhere to collect our money. Or perhaps it was all on the honor system.

Skeleton Coast National Park

This whole area of the northern desert coast, stretching from the Kunene River to the Swakop River has been called Skeleton Coast. This area has been described as the place God made in anger. And colonial sailors called it “the gates of hell.” This was partially due to all the death that occurred here. Partially due to the desolation and remoteness of the place. Partially due to the fact that it is miles upon miles upon miles of nothing but flat sand and the ocean.

We finally hit the Skeleton Coast National Park. We approached the gate which had two skeletons on it, bought a permit, took photos of the whale bones and set off again. I think I said it before, but it bares repeating. This area is remote, desolate and full of beauty. It is a protected area because the coast if full of diamonds. Yet Charles would not stop to let me find some! (J)

There was nothing but sand for miles and all of a sudden there was a lagoon. Clearly it had rained here.

Brown Hyena

We kept driving and then, between Hentis Bay ad Torro Bay, at the mouth of the Huab River, Charles, eagle eyes, suddenly pulled over and quietly and calmly said, “There is a hyena.” Now this was one of the animals we had not seen in Botswana, and we had mentioned we would like to see one. And Charles obliged. We quietly got out of the car and tiptoed over to where we could see him better. As the camera clicked away, he ran across the road, in front of our car and to the other side, heading towards the ocean. Charles said, “Let him go.” We waited for a bit, and then followed, our feet leaving deep footsteps in the soft gravelly sand which was filled with sharp black rocks giving it the speckled dark look, and shell fragments and little white quartz which gave it a shine.

The hyena was on the beach eating, probably a seal cub. Charles told us how rare it is to see a brown hyena during the day and at the ocean. We were very lucky. We watched him for a while and he finally noticed us. He started walking towards us to explore. But then he thought better of it and went back to his eating. He probably wanted to protect his food. We watched some more until he finally slinked away.

And that is why I travel with a guide. We met lots of folks like Paul and Michelle from SW England. They were a lovely couple. But they were self-driving. I would never have spotted the hyena and if I had, I never would have thought, or had the courage, to follow it.

So what do we know about the brown hyena? The brown hyena, also called a strandwolf, is one of Africa’s largest, and most rare, carnivore. It is found only in Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa and therefor is one of the rarest species of hyena. Brown hyenas are distinguished from other species by their long shaggy coat and pointed ears, a dark brown coat and a short tail. Their legs are striped brown and white, and adults have a distinct cream-colored fur ruff around their necks. That is exactly what we saw. There are about 800-1200 in Namibia, out of about 4000 in all of Africa. Brown hyenas live in clans and the male helps the female raise the cubs. But in general, they are usually seen on their own, as we saw ours, searching for food. Brown hyenas seldom hunt small or medium-sized mammals and usually rely on carcasses of animals, which died naturally or were killed by other predators. That must have been the case with the seal cub we saw the hyena eating.

Back on the Road

The terrain changed again as we approached Torra Bay. There were now slight undulations and the dunes were no longer flat. All of a sudden, everything disappeared. We couldn’t see a thing. It was an epic sandstorm. Luckily all our windows were closed. And just like that, it stopped and everything was flat again.

We drove along our merry way and ran into a detour. Seriously? A detour? There was nothing here and there were no other cars. But there they were – trucks fixing the road. The gravel turned to dirt as we veered around the detour and then we were back to gravel again.

There were no trees. There was nothing green, other than a bit of lichen now and then. Everything was bare. It was just sand and rock. As we drove the only sound was that of the rocks being thrown up by the tires and hitting the underside of the car. Ping. Ping. Ping.

Saltbushes

We came over a small hill and now there were some green saltbushes (official name ganna, the same family as beetroot and spinach) on the sand mounds with white dunes up ahead. White dunes growing out of a black base of gravel. The saltbush is resistant to saline and thus can grow here. Its stems and leaves were a dull and light-green to greyish and the leaves were tightly grouped on the stems and shoots, giving a knobbly appearance.

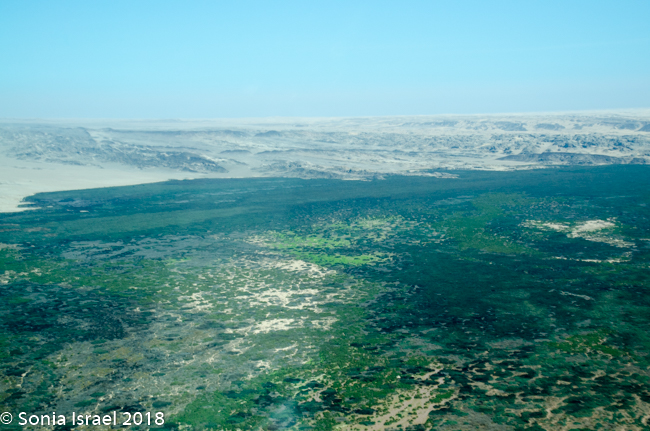

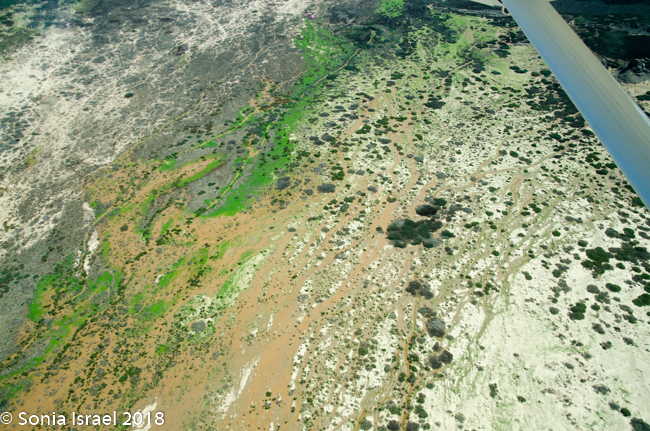

The white dunes were now paralleling us. Tall green reeds appeared and there were green mounds, almost like warts, on the sand. There must have been a river here that recently dried up for there to be so much green growth.

This whole place, the whole Skeleton Coast, looks as desolate as the moon. But unlike moon it is teeming with life. Shrimp for the flamingos in July. Oryx. Lions. Hyenas. Other organisms. Its just that we can’t see most of them.

Terrace Bay

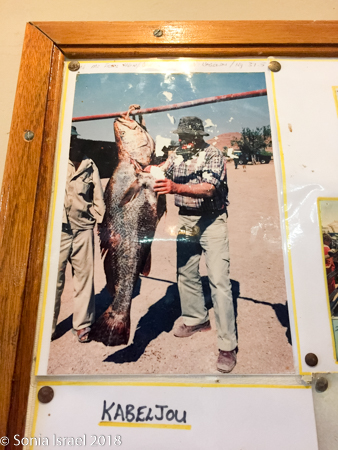

We finally reached our destination, Terrace Bay. This would be our home for the night as it is the only place one can stop along the Skeleton Coast. Terrace Bay is known for fishing and many people, especially from South Africa come here to fish. But to us it looked like a ghost town or a deserted town. Charles called it spooky. I called it creepy. Their website describes it as: “…an angler’s paradise offering an exceptional coastal experience …The resort is located on the coast, set in an undisturbed and peaceful spot, surrounded by the majestic dunes of the northern Namib Desert… You can hike, bird watch, spot game or witness breath-taking sunsets from atop the dunes.”

Well, when we pulled in, it looked totally deserted. It wasn’t as it turns out, but it looked that way. The registration desk is in a large hall with a pool table, lots of empty space, a bar and a few tables. After registering and leaving a deposit for our keys (like we would want to take them?), we went over to the bar for some lunch. The menu had some appealing items. But when we asked for something the answer seemed to always be – “we are out of that. Waiting for a delivery in the next few days.” We finally settled on cheese toast for Andy and me, and a Russian (sausage) for Charles, as those were really the only choices. There were flies everywhere. Creepy.

We drove over to our rooms which were as simple as could be. Two beds. A refrigerator with a coffee pot. A bathroom. It felt really like a campground. But it was clean. And it was quiet. And we were only here for one night. And it was the only option.

Andy and I unpacked a bit and went for a walk along the water. The waves splashed on the rocks. Birds were flying everywhere. There were all these shells on the ground. And as the sun began to set, it was indeed a “breath-taking” sunset. And then it was dark, dark, dark and we got to use our headlamps.

We walked over to the restaurant for dinner and discovered there really were other people here. The walls of the restaurant were covered with signatures. When I say covered, I mean there was barely a free centimeter. We wanted to add ours, but were told they had no more pens. Seriously?

At dinner, there were several couples and one group of four men on a man’s fishing trip. Clearly repeaters. Seemed we were the only ones just stopping by on our way up north. There were no choices for dinner. You ate what you were served. But everyone was very friendly. And the food was good. So overall, no complaints.

That night the sky was spectacular, and I practiced taking photos of the sky. Not good enough yet.

The next morning, after breakfast, we left Terrace Bay behind. It had been comfortable and warm and clean. And we did get a good night’s sleep. So not creepy anymore.

The Terrain Keeps Changing

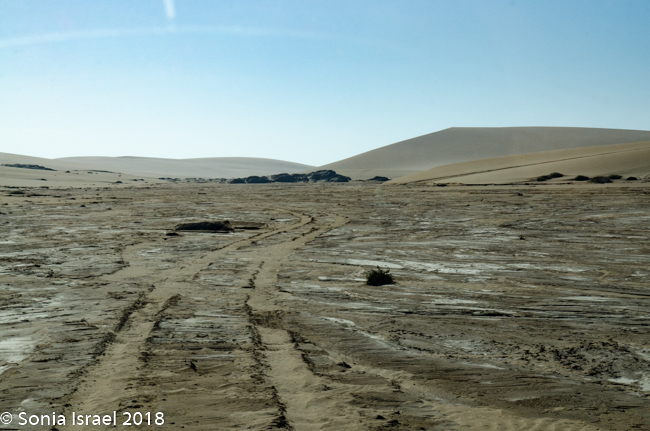

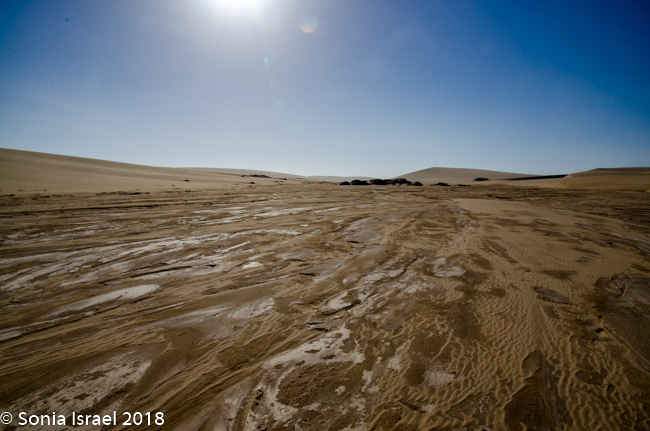

As we drove the terrain was constantly changing. This time it changed from white to black to red. Was it because of wind currents? Rain? Rivers? Minerals? All of the above. But the change was really so sudden like someone drew it with a ruler or protractor. And the road, which was all sand with stones, would go from smooth and easy driving to rough terrain that made our insides feel like milkshakes, to soft sand to deep grooves that without a 4×4 you would get stuck in.

The car was quiet this morning. Charles drove like he owned the road, which in some way he did, speeding up and slowing down as the terrain permitted His eyes constantly scanning, looking for wildlife.

And I just tried to take in the vastness of this moonscape. The flatness, with a small hill now and then. The sun rising in the east as we headed north, throwing our car’s shadow onto the ground as if another car was racing us.

And the whole time the waves of the Atlantic crashed one after the other onto the shore.

We began to see some remnants of whales, reminding us why this is named skeleton coast. We drove over the area where the mouth of the Hoanib River meets the ocean. We would camp near this river tonight, but many, many miles from here. Charles again drove off the road to another lagoon to look for flamingos, but they had all flown to Etosha to find a mate.

Our plans for today changed. We were supposed to drive to the Hoanib River for our camping experience. But there had been some heavy rains and the roads were flooded. It would take a few months for them to dry out. Driving meant heading back down south, cutting across and then coming back up further east, on the other side. This would be about a 10-14 drive. So Charles arranged for us to fly there and he would drive and meet us the next day. We would spend the morning with him going to see the seals, the Skeleton Coast Museum, some shipwrecks and sand dunes and then fly.

Sand Dunes

We started with the sand dunes. Charles knew this area like the back of his hand as he spent two months here in 2015, scouting out the area and creating roads for the then newly built Hoanib Skeleton Coast Wilderness Safari Lodge (the number 1 camp in Namibia and number 2 in all of Africa). We were looking for lion tracks in the pristine sand, but instead we found loads of springbuk (a type of antelope common in Africa). Charles taught us that in young springbuk, the horns go forward, in adult they turn inward, and the older they face backward. Always learning.

We drove on “Charlie’s Road” as it is now called, veered east past the airstrip (in the middle of nowhere) and came face-to-face with a sand dune. Charles deflated the tires and up we went.

It was pristine. The designs in the sand looked like the waves of the ocean. Or abstract paintings. Curves, curves and more curves. In every direction, whereever the wind had blown the sand. There was sand forever which no marks except our tracks. And our shadows as if we had three additional visitors. And we were so small, infinitesimal, in relation to the vastness of the desert around us. We were on top of the world.

And what does it feel like to drive on a dune? Watch…

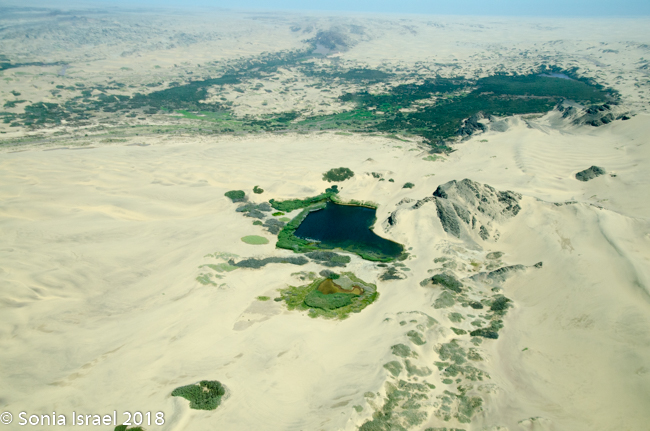

We left our vehicle and walked, and it was just our footprints. And then, right in front of us, was an oasis. The real deal. Not a mirage the way it had been in the Gobi (see my post on Mongolia). The Klein Oase and Auses Spring. A large water hole surrounded by gray and green stripes of grass. White-breasted and cape cormorants were floating lazily all around. I wanted nothing more than to jump in but refrained myself. Instead I just stood there and tried to memorize the beauty of the place. There were no sounds except for the birds. Not another soul was around. It was just white sand as far as the eye could see. And the blue, blue sky. The deep blue-green water. And the green and gray grasses. Colors in the midst of the desert.

Charles was so excited to be back that he kept trying to take just the right selfie. “Charles,” I said, “I do have a real camera here!” So he let me take his picture, of course posing with a map of Namibia. A map? Yes, Charles would fold his index finger and stick out his thumb. And there it was, the map of Namibia.

We came off the dune and continued on the riverbed and then went up another, taller dune with a vista of just more dunes everywhere you looked. Charles walked to the edge took off his shoes. posed with his arms out, and before I knew it, jumped  and disappeared. What happened to him? I ran over as fast as I could – it is not easy running in soft sand – and peered down. And there, just a few feet away, was Charles, knee deep in sand, laughing. I made him do it again to I could photograph him flying. And as much as I wanted to try it, I didn’t have the nerve to test my knees.

and disappeared. What happened to him? I ran over as fast as I could – it is not easy running in soft sand – and peered down. And there, just a few feet away, was Charles, knee deep in sand, laughing. I made him do it again to I could photograph him flying. And as much as I wanted to try it, I didn’t have the nerve to test my knees.

It was time to drive down off the dune. Charles stopped at the steepest possible spot, we held our breaths and slowly drove down. Such excitement!

On the way out we saw more Spring Buks. They almost blended into the  background, better to hide from the lions and cheetahs, their main predators. Nature.

background, better to hide from the lions and cheetahs, their main predators. Nature.

We also saw a purple stripe in the dune which was a line of garnet sediment.

Namibian Cape Fur Seals

We drove back past the airstrip towards the water’s edge again. Our next stop was at the coastline to view the Cape Fur Seals, whose closest relatives, surprisingly, are brown bears. There are about 2 million seals here as they have no predator here (there are no white sharks here). So the Namibian government culls the seals twice a year. The only other country in the world to cull seals is Canada. It is only the males and the cubs that are culled. The females are always pregnant, so they are never culled. Always pregnant? Their gestation period is 8 months. The males are usually gone for 8 months at a time searching for food. So they implant an egg but fertilization is delayed for up to three month. Thus, she is always pregnant.

The coast line was covered with seals with hardly a place to walk that hadn’t been visited, that is, that wasn’t covered with excrement. And with fur as the cubs, of which there seemed to be hundreds, were shedding. The seals were squealing and wobbling all over the place and frolicking in the water. The noise was deafening. The smell was overwhelming, bombarding our senses and permeating every pore.

- Seal fur

The gulls were sunning themselves, or taking off and flying in groups, white and gray against the deep blue sky.

And all along the coast there were old whale bones and rusty diamond mine equipment. It was like a junkyard full of old remnants of the past.

Museum in the middle of the desert

After watching for a while we walked over to the small museum filled with specimens from the area. Penguin skulls. Black rhino skull. Whale bones. Lower jawbone of a humpback whale. Whale baleens which looked like palm fronds. Elephant skull and teeth. And so much more all in this small one-room museum.

Suiderkus and Dunedin Star

We drove out to see another shipwreck, the Suiderkus. This was a relatively modern fishing trawler which ran aground on her maiden voyage in 1978, despite having a highly sophisticated navigational system. After a few months most of the ship had disintegrated but a large portion of the hull was still sitting on the beach. Pieces were strewn everywhere as the water bombarded the remains day after day, month after month, year after year.

Charles told us the story of the Dunedin Star, a British cargo passenger liner. In November of 1942, with 106 passenges and crew on board, it was stranded at the mouth of the Kunene River. They managed to take 42 people to shore while the rest were rescued by the crew of another ship. A plane was sent from the Cape of Good Hope to land with supplies for the survivors. But it got stuck in the sand. A tug boat was lost also trying to rescue them. Finally, a land rescue convoy succeeded in rescuing the survivors. Ah, the Skeleton Coast.

Garnets

The sand around the ship wreck was glistening and sparkling and purple. The sand was full of sediments of garnets. Wish I could just collect them.

Lunch at the Water’s Edge

A picnic lunch was then served along the water’s edge. Other clients from the Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp had flown in to also see the seals and the dunes. We all sat down at a long table with a white table cloth, all seats facing the water. There was a sink set up for us to wash our hands. Wine and beer were offered. And lunch of veggie or beef wrapped in a tortilla, green salad and tuna salad served in jars and fruit for dessert.

Flying over the dunes

And then it was time to gather our bags and head for back to the airstrip for our bush plane flight to our next destination, Hoanib River. We boarded the small plane and I got to sit next to the pilot. We started by flying west to the coast, and then south along the water’s edge. After a bit, Steven, the pilot, headed east and then north. We flew over the dunes. We flew over the area that had been flooded and that resulted in the flooded roads that caused us to fly. We flew over a the oasis we had visited just a few hours before and over a second smaller oasis, known as Charlie’s Oasis. Yes, after our Charles. And then we could see the lodge, the Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp, and the small airstrip where we landed a few minutes later. Somewhere out there we would be camping for the next two nights.

We were met by Gerhard, our guide and cook, no, not cook but rather our chef for the next two days. And now our friend. Gerhard was ready to start the drive to the campsite, but we requested to see the Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp first. We were greeted by a cold, wet towel to freshen up, and a delicious glass of homemade refreshing sparkling lemonade. One tent was empty as they guests had not yet arrived, so Gerhard took us on tour. We sat in the common area for a bit relaxing.

And then it was time to climb back into the car and go find our campsite. And that will be start of the next chapter.