July 26, 2018

You can’t talk about Medellin without talking about drug wars and politics. So in this chapter I will describe the history that Medellin, and the rest of Colombia, fought against, and I will tell you about Comuna 13. It is a fascinating story of civil war and survival.

Medellin was once known as the most dangerous city in the world. Why? Because of an urban war begun in the 1980s between the drug cartels. It gets complicated but stay with me and I will try to explain (and hope I get it right). But I will explain it through the eyes and ears of the locals, the people who lived through that frightening time.

La Comuna 13

This afternoon, after lunch, Juan Carlos picked us up and we set off for our tour of Comuna 13. A comuna is a mountainside barrio. This was once the most dangerous place in all of Medellin, and Medellin was the most dangerous city in the world, known as the murder capital of the world. La 13, as it is affectionately called, has a deep tradition of being an organized community filled with a strong spirit of resistance. And so it is no longer a dangerous place. Not anymore.

Guillermo, our driver, dropped us off at the bottom of a steep hill where Juan Carlos, Andy and I met up with Johana, co-owner with her husband Sebastian of Tour Ruta 13. Johana would be our guide as we walked around Comuna 13.

Guillermo, our driver, dropped us off at the bottom of a steep hill where Juan Carlos, Andy and I met up with Johana, co-owner with her husband Sebastian of Tour Ruta 13. Johana would be our guide as we walked around Comuna 13.

Comuna 13 is also called San Javier, and is an over-populated, low socioeconomic barrio hugging the hills in the western part of Medellin. Unlike Europe, where the hills are reserved for mansions and the rich, here in Colombia (like in Mexico), the hills, while having beautiful views, are covered with thousands of crumbling brick and cement houses covered with corrugated metal roofs. The houses look like there were haphazardly heaped together, although the colorful walls and the green trees, and now the colorful graffiti, bring a quiet beauty to the place.

We walked up a block or two and stopped across from some murals (graffiti art; see below), at the bottom of a zig-zag stairway, trying to get a bit away from the other groups of walking tours. This is a popular place, probably one of the most important to visit in Medellin. Why? Why was it so dangerous? Why so popular? This is what Johana was going to teach us.

And thus the wars begin

In the 1940s farmers immigrated in large waves to the city of Medellin, trying to escape the conflicts in the areas of Antioquia, as this department (like a state) is called. More than 1500 families settled in La Comuna 13. They built makeshift houses made of wood and aluminum, on the hills, with no planning and no building controls. It still looks like they are clinging to the mountain. And thus began the poor neighborhood filled with families with little skills other than farming and construction. Their water came from contaminated streams and rivers. Their electricity, such as it was, was stolen. It was the perfect storm for the growth of gangs and guerrillas.

Pablo Escobar

You can’t continue in the story without learning about Escobar. Escobar was a drug lord and narcoterroirst. He grew up poor but as he gained more and more money, he would come to visit the poor. And he would pay children to become soldiers in his “army.” And so he became known as a Robin Hood by the poor population as he would steal, kill, extort, all in the name of helping the poor. His mother had taught him, “whatever you do, don’t get caught.” Not, “do good.” “Don’t get caught.” His career in crime began when he dropped out of the university and got involved selling contraband cigarettes and fake lottery tickets. In the 1970s, he began to work for various contraband smugglers, often kidnapping and holding people for ransom before beginning to distribute cocaine himself. He established the first smuggling routes into the US, and as the demand for cocaine rose, his smuggling activity increased. It is estimated that in the 1980s, he shipped 70-80 tons of cocaine to the US each month. 70-80 tons a month! In short, he ran a drug cartel which supplied about 80% of the cocaine that was smuggled into the US, making about $22 billion a year in personal income. Thus he was called the “king of cocaine,” with a net worth of $30 billion by the early 1990s, and thus the wealthiest criminal in the history of crime as well as one of the richest men in the world.

His drug network, the Medellin Cartel, competed with rival splinter cartels, many of which grew from those originally loyal to Escobar, both domestically and abroad, and this of course led to massacres and the murders of police officers, judges, locals, and prominent politicians. In other words, the city of Medellin became the victim of terror as a result of the drug wars.

In 1982 the US asked for Escobar to be extradited. Instead, Escobar ran for congress. He supported politicians with all his money, so who would vote against him? In fact, he gave everyone a gift of money to vote, and then threatened them all with death for their whole family if they didn’t vote. But Escobar did good things too. He was responsible for the construction of houses and football (soccer) fields in western Colombia, which then also gained him notable popularity among the locals of those towns. He was crazy for power and killed his opponents. He paid the locals $2000 if they killed a policeman. So, poor people made money – more than they ever saw, by killing the police. And of course he won the election. And once he won, he created a law against extradition.

And then, in 1993, Escobar was shot and killed in Medellin, his hometown, some say by the Colombian National Police, others that they don’t know who killed him. It was one day after his 44th birthday. And there were many people, especially among the city’s poor whom Escobar had aided while he was alive, who mourned his death, and over 25,000 people attended his funeral. There are still some who consider him a saint and pray to him for receiving divine help.

But Colombia still had guerrillas.

The Communist guerrillas arrive in Comuna 13

Johana continued.

The violence began with local gangs who came into the area threatening the families for money so they could buy drugs. If you didn’t cooperate, you were killed. But then things got really bad. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Communist guerrillas arrived.

Johana, who is now 25, was telling us these stories not from books she read, but from her own experience. She spoke in Spanish, and Juan Carlos translated for us. She was 10 when the next wave of violence began. The Communist guerrillas came in, displacing the local gangs. Why were they interested in La Comuna 13? Several reasons, Johana explained when I asked that question. One, they were poor and vulnerable. Two, they were just on the other side of the mountain from the main highway, the San Juan Highway, which leads to the Pacific Ocean, thus providing easy transportation for drug trafficking. So the Communist guerrillas came in. They would knock on a door and say, “This is now my house. You will cook for me. You will pay me. You will work for me.” These guerrillas took total control of the area. They were the judges who settled disputes. They decided who lives and who dies. Who was a thief and who was a victim. They stole. They raped. They killed. Johana said, “Thank God, they did not come to my family’s house.”

And then there was FARC, ELN and the paramilitary groups

As we stood there listening to her story, it began to rain. We ran up the street and stood under an overhang outside of a small convenience shop. And we waited for the downpour to let up. A few minutes later, it did just that and we continued up the hill.

And her story continued.

At this time, in addition to the Communist guerrillas in Colombia, there were also the FARC, the ELN and the paramilitary groups. All illegal armies. The FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army, was its own guerrilla movement, a terrorist group. Their goal was anti-imperialism and they funded themselves though kidnapping and ransom, extortion, and drug trafficking. The ELN was the National Liberation Army, also a terrorist group. And the paramilitary was secretly formed by the government to do all the terrorist types of activities that the government could not legally do. The army would kill innocent people and say it was FARC that did it, just to make themselves look good. But the army never was punished because they said the president told them to do it. Between these groups, there were thousands of thousands of deaths. And much of this fighting and terrorism took place in Comuna 13.

The personal stories

I asked Johana how she was personally affected. Schools were often closed for days or weeks at a time due to the terrorism. Often they could not leave their homes to get food. They would sleep under their beds to avoid stray bullets. And around them, the terror continued.

Her husband, Sebastian, who also grew up in Comuna 13, had more stories. One night “they” came and took his father. The family never knew why, but there were many poor people, who would be paid 50,000 pesos to turn someone in, so they would point out anyone they might not like. But Sebastian’s dad was lucky. The neighbors came out in his support, telling the guerrillas that he was innocent and never worked with any of the guerrilla groups. And an hour later, he was back home. Not the typical story. Most people just disappeared, killed, and the body disposed of.

He also told us that when he was younger, growing up during all the violence, he was very innocent. He saw the army uniforms with the letters “PM” on them, and was frightened of them. He thought ‘PM’ stood for ‘evening’ because they always patrolled at night and that’s when they did their killing. It stood for Policia Military.

Sebastian is now one of the leaders of the community, acting as a middleman between the locals and the mayor.

I asked them both the obvious question. “Why didn’t you just leave?” And the answer should have been obvious to me too. They couldn’t leave. Where would they go? They had no money. They had so little. And if they did leave, they would lose their property.

And part of the answer also lies in racism. There was racism then and there is racism now. But in Colombia, racism is not about color. It is about social class. There are six levels: Level 1-2 very poor. Level 3 lower middle class. Level 5-6 upper class. And Comuna 13 was level 1.

Operation Mariscal

And then in May of 2002, the Colombian Army decided to attack the guerrillas with Operation Mariscal (in English, Marshall). They came in with 1000 soldiers and tried to flush out the guerrillas. But of course, they had no idea who were the guerrillas and who were the innocent victims who lived there. It was a complete failure with the innocents being the victims. Nothing changed and nothing improved.

Operation Orion

Then in October of 2002, came Operation Orion, the last and largest military intervention in Comuna 13. This time the army sent in 2000 soldiers and two Blackhawk helicopters. Sebastian said that living during Orion felt like being in a movie with helicopters shooting. In the midst of the fighting, one mother (mothers are always the heroes in these stories), had two sons injured and decided she had had enough. She waved a white bed sheet through the window, yelling to let her out to take her boys to the hospital. A few minutes later, as an act of solidarity, other neighbors did the same thing, waving white sheets of surrender. This led to 12 hours of a cease fire. But at the end of the 12 hours, the fighting started again. But the Blackhawk helicopters were frightening, and the guerrillas got scared and escaped into the mountains. Comuna 13 was free. Free but still very poor, like any barrio anywhere in the world. And not without consequences. In the 10+ years of the violence, of the war, 45,000 people were killed.

Escaleras Electricas – Escalators save the day

The government was feeling a bit guilty about the conditions of Comuna 13 and all the residents went through. How do you fix that? The government began to look for ways to improve life in this area. Johana led us to the Escaleras Electricas, electric escalators which changed their lives. From the bottom of the mountain to the top there are 362 steps. For the poor of this area to work, it would take them many hours to get down the mountain and into the city. The roads were steep and many neighborhoods had such narrow streets that cars could not get through. This left the community isolated.

The government’s solution was to build a giant quarter mile orange-roofed electric escalator that climbs the mountain in six sections. The whole trip takes six minutes. Quite a difference from the previous hours. This enabled the locals to get down the mountain and get jobs. And these escalators are credited with bringing peace to the community. The escalators and the graffiti (see below).

But in order for the escalators to be built, 48 houses had to be destroyed, 48 families displaced. Sebastian helped those 48 families by raising money for them to use for renting other houses.

I asked Johana how the escalators helped her. She replied that she now works in the tourism industry. The escalators, and the graffiti art, have brought lots of tourists into the area. They operate the walking tours, they have a small convenience store, Crèmas Dona Consuelo, on top of the mountain where they sell special popsicles (see below), and she is getting ready to open a coffee house. The neighborhood is now under control of the community and they all take great pride in it.

Hector Pacheco

Comuna 13 is covered in graffiti art. And it all started after Project Orion, with Hector Pacheco, nicknamed Kolacho. Kolacho was a hip-hopper who lived in Comuna 13. He believed in music and in art and became a young community leader in the midst of the war – the drug war. He believed that the best way to keep children from being recruited by the guerrillas was to give them something to do. Dance and paint. Paint and dance. And thus he started a peaceful revolution.

What happened to Kolacho? One evening in August 2009, he gave a public lecture asking the young children and teens in his neighborhood to use hip-hop as an instrument for non-violence. One week later, he walked down the steep hill of his Comuna 13 to wish his aunt a happy birthday. As he started back up the hill to head home, he was gunned down from someone on a motorcycle. He was 20 years old. Some say it was the paramilitary that shot him. But whoever it was, his killing did not stop the youth from using music and art to bring peace to their community.

As one child would paint, others would approach him or her looking for a safe community to join. And each then learned the art. This became a sort of art therapy and from that, and to honor Hector Pacheco, Casa Kolacho was born. Casa Kolacho is a non-profit program, a cultural organization, that promotes the hip hop culture with all the youth in Comuna 13.

We ran into some of these children. Such beautiful faces. Such beautiful smiles. Such hope for the future.

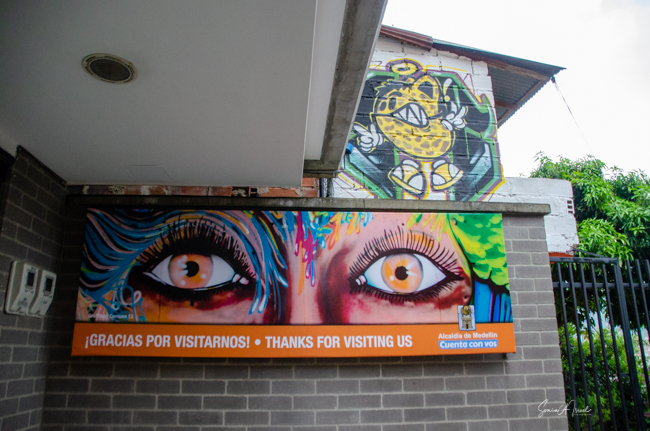

The art, the graffiti, has become an attraction here, bringing tourists which brings money. But the art has also brought peace and protected the youth. Each piece of art is full of symbolism. Many of the pieces focus on eyes – the windows to the soul but also representing that there is no need to hide. And the art brings color and life to every empty wall in the comuna.

Graffiti Art

We saw graffiti at the landings of the different sections as well as on almost any other wall. As we approached the bottom of the first section of the escalator, Johana stopped to have us look at a large mural of a black woman’s face. Her mouth created a heart. And her neck was formed like the fetus of a baby. Life and love. Not all the murals were painted by the local youth. This one was painted in 2014 by Paola Delfin, a Mexican female artist, who visited Comuna 13 and wanted to paint something as a gift to the community.

This helped the art become a way to beautify the lives of the local residents. And as I said, there is now graffiti art everywhere.

I can’t describe each mural we saw. But a few need some explanation. At the bottom of the hill are elephants waving white flags, representing the white flags of Operation Orion but also representing family, and since family is a treasure, the elephants are painted in gold.

In the middle of the escalator sections is a very large mural which tells the story of Operation Orion. This mural is like a history book, teaching all who see it what happened in those few life-changing days.

The murals represent sorrow, loss, love, redemption and everything in between. They are colorful and they bring life to the community. And they tell the story of what happened. Messages. That is how people know their story, their history.

Community

We made our way up each escalator. Johana constantly stopped to say hello to her neighbors. We ran into her mother-in-law. She kissed the guards monitoring the escalators. This is a tight knit group of people.

After hearing the stories of the different murals, and taking lots of pictures of the huddled houses on the face of the mountain, we started heading back down.

Cremas Dona Consuelo

We stopped half way at the Cremas Dona Consuelo, Johana and Sebastian’s store. They sell postcards and t-shirts and popsicles. But not just any popsicle. They hand-make ices in small plastic cups. For the coconut one, they shred the coconut. For the fruit, they wash and peel and prepare. It is a family affair. Each cup is filled with the frozen fruit and has a stick sticking out of it. For most of the flavors, you just pull the stick with the ices out of the cup and enjoy. But for the mango, there is a whole procedure, which Sebastian danced out for us.

Survivors

Johana escorted us back down the mountain where Guillermo was waiting for us. We hugged good-bye and we took our leave.

We have traveled the world. In so many places there are survivors of horror and pain. There are the Holocaust survivors. There are the survivors of the Pol Pot horror in Cambodia. There are so many others. Comuna 13 was also one of those places. I looked at Johana and Sebastian and I saw survivors.

Cementerio La America

On our way out of Comuna 13 we passed the cemetery. One has to wonder how many bodies are buried all over the hills of Comuna 13 given all the violence that happened here. I don’t know who is buried here, but I do know that the community has made it a beautiful place which is what cemeteries should be like. A place to visit loved ones, a place filled with flowers and beauty. We didn’t step inside, but from the outside, it was lovely.

And now?

So what is the current status of all this violence in Medellin and in Colombia? In 2016, the President of Colombia made peace with FARC. The agreement was they would not get jail time, but had to provide education and social work for the villages and villagers they had hurt. After all, many of the problems in Colombia can be traced to a corrupt government and a lack of education. The people however, voted against this in the elections, but the agreement was made anyway. On June 27, 2017, FARC disarmed itself, handed over its weapons to the UN and ceased being an armed group. As part of its agreement with the government, FARC became a legal political party, the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force. Oh, and as it says in the history books. the president, Juan Manuel Santos won the Nobel Peace Prize “for his resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end, a war that has cost the lives of at least 220 000 Colombians and displaced close to six million people.”

However, there are many who disagree with the peace agreement, feeling that the guerrillas should not go free. The story is not over yet.

Note: If you want to learn more about the history of Comuna 13, there is a documentary, La Sierra, directed by Scott Dalton and Margarita Matrinez. The trailer is available on YouTube and there is a DVD you can buy on Amazon.

Leave a Reply