August 22- September 2, 2022

There are lots of reasons to visit Borneo. But one of the main reasons is to see orangutans. Those big, furry orange/red creatures. My friend Ruthi and I traveled with Natural Habitat Adventures (@NaturalHabitatAdventures) exactly for this reason, I with my two OM System D-E M1 Mark III camera bodies, one with an Olympus 12-100 f4 lens and the other with an Olympus 100-400 f5.6 lens. It was a 12-day trip all around the country, guided by Expedition Leader Harsha Jayaramaiah and local guide Bedley Asun. There are posts on Kuching and other cities. There are posts on other animals we saw. But this post is all about orangutans.

Orangutans are great apes, of which there are three types: Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli. We, of course, were searching for the Bornean. But before I get into our adventures, here is some background on these magnificent apes (as usual, probably more than you ever wanted to know…).

Orang Hutan

The name orangutan comes from the Malay language and means “man of the forest” (orang meaning person and hutan meaning forest).

The Bornean orangutans are critically endangered with only about 105,000 left. Bornean orangutan populations have declined by more than 50% over the past 60 years, and the species’ habitat has been reduced by at least 55% over the past 20 years. The severe decline in the population is primarily due to us humans who poached them for bushmeat (a practice which decreased once children were taught in schools about the importance of conservation and they then educated their parents), killed them in retaliation for consuming crops, illegal pet trade, and perhaps most importantly, due to habitat destruction and deforestation for logging and palm oil cultivation (more on this later).

What do they look like?

Orangutans are known for their distinctive red fur. They spend most of their time in trees which makes them easier to spot against the foliage. They have long, very powerful arms and they use their hands to grasp and swing through the branches.

Adult male orangutans stand up to about 4.5 feet and can weigh up to 200 pounds while the females are smaller at about 3.5 feet and up to 82 pounds. Dominant males have cheek pads, called flanges (see pictures below) and a throat sac, both of which are used to make loud calls to attract females.

Both male and female orangutans have proportionally long arms, with an arm span of over 6 feet. But their legs are very short. And as I mentioned above, they are covered in long red hair, that starts out as bright orange when they are young (see the pictures below) and darkens to more of a maroon or chocolate color as they get older.

Their hands are very interesting, with four long fingers and a much, much shorter opposable thumb. This allows them to have a strong grip on the branches as they “fly” from tree to tree. And we saw them swing through the trees and it was really did look like they were flying. When at rest, their fingers are curved which makes them look like a hook. Since the short thumb stays out of the way, they can securely grip all size of objects. Their feet have four long toes and an opposable big toe which allows them to use their feet as hands.

Unlike other great apes, orangutans rarely come down to the ground where they are more cumbersome. But when they do, they walk by bending their digits and walking on the sides of their hands and feet, unlike other apes who walk on their knuckles. We got to see one walk right by us, carrying his stalk of bananas. I wasn’t afraid at all. He ignored me (and all the rest of us standing around) and we just watched in awe (see below for the pictures).

Mothers and their Offspring

And what happens once that male attracts a female? She can start having offspring at about age 15 with 6-9 years between births. During this time, she tends to avoid the males. The females take care of their young, carrying it while traveling, suckling and sleeping with it. During the first four months, the two are in constant physical contact, with the infant clinging to its mother’s belly. At about age 2, the young one begins to move away from its mother, traveling through the canopy holding hands with other orangutans, called “buddy travel.” They may travel away from their mom temporarily, but always return until about age 6 or 7.

Typically, orangutans live over 30 years both in the wild and in captivity.

How do they spend their days?

Orangutans spend most of their time either eating, resting or traveling. They begin their day by eating for 2-3 hours. They like to eat wild fruit but will also eat vegetation, bark, honey, insects and bird eggs. They slurp water from holes in the trees. When they are done eating, they rest. Then, in the afternoon, they may travel by swinging through the trees. In the evening, they begin building their new nest for the night. Yes, like chimpanzees, they build a new nest, in a new location, every night.

Nesting

On one of our drives along the Kinabatangan River in the Sabah area, we saw an orangutan lying down in her nest, and reaching out an arm to grab fruit from the branches surrounding her. We watched for quite a while as it was fascinating to see her in her nest. But here was my question: What was she doing in her nest in the afternoon? My answer: She was phase advanced (which means her biological clock was out of sync with the environment) and she went to sleep early and likely woke up earlier than most of her species.

The nests is done in a very specific sequence. First, they have to find a suitable tree. Although you would think any tree would do, the orangutans are very choosy about the site. They then begin to build a foundation by grabbing the largest branches under it and bending them so they join together. Then they do the same thing with the smaller, leafier branches which creates a mattress. The orangutan then stands up in the partial nest and braids the tips of the branches into the mattress, which increases the stability of the nest. They then make their nest “comfortable” by creating what we would call pillows, blankets, roofs and even bunk-beds.

The young orangutans watch their mothers build the nest each night and practice building their own and thus learn how to do it correctly. Only when they can build their own nest, can they become independent.

And they are smart

We share about 96.4% of genes with orangutans and like us (or maybe unlike us?), they are very intelligent. They communicate with each other with sounds. As mentioned above, the males will make long calls to attract females, but also to let other males know about their presence. The calls start with grumbles, peak with pulses and end with bubbles. When they are trying to intimidate each other, both males and females will have what’s called a “rolling call” which is a series of low frequency noises. When they are uncomfortable, they produce a “kiss squeak” where they suck in air through pursed lips.

Mothers communicate with their offspring with different gestures and expressions such as beckoning, stomping, lower lip pushing, object shaking and “presenting” a body part. These communicate goals such as “acquire object”, “climb on me”, “climb on you”, “climb over”, “move away”, “play change: decrease intensity”, “resume play” and “stop that.”

They have also been seen using tools.

Semenggoh Nature Reserve

On our second day in Kuching (please see the post on Kuching), we were loaded onto a bus and headed 12 miles to the Semenggoh Nature Reserve for our first encounter with orangutans. The Semenggoh Nature Reserve is a natural habitat established in 1975 as a sanctuary for orangutans who were injured, orphaned or had been (illegal) pets, most between the ages of 1 and 5 years old. The orangutans living here roam the forest and are free to go wherever they want but have been trained to come back to the center during the morning and afternoon feeding times where they get a free meal from the caregivers. Nevertheless, during the forest fruiting season, they don’t always come back. Over the years many have been released and now are part of a semi-wild colony in the reserve.

I do need to mention that the vegetation and other creatures around there were also fabulous.

- Capers

Afternoon feeding

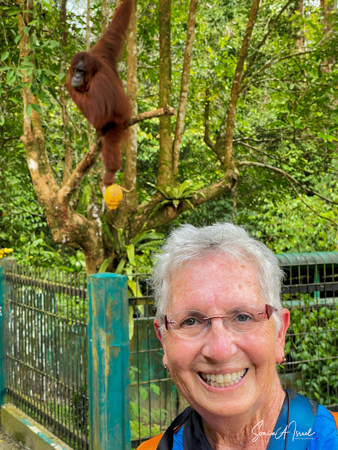

We got there in time for the afternoon feeding. We stood around, behind a low fence, looking up into the trees. We saw one or two orangutans in the trees and were so excited to take pictures with them.

There were two more way up in the trees, climbing around using their long limbs.

And before we knew it, an orangutan swung down from the trees and made her way down towards the fruit that was sitting on a platform.

Some of the caregivers were handing out coconuts and other fruit for them to eat. And then more and more orangutans came forward. While there are 26 orangutans in the sanctuary, we saw six: Anuar-Alfa male, age 26, Suduku-Female age 51 (called the grandma because she is one), Ganyah-Male, age 14, Anakku-Male, age 16, Ruby -Female, age 9, and Jubli -Male, age 9.

They were swinging through the trees. They were sitting and eating. They were grabbing the food and climbing up, high into the trees.

One of them had lost an eye, likely in a fight, but seemed to do just fine. And then, the caregiver said, “Everyone move back.” As I mentioned above, one of the orangutans decided to come down and walk amongst us. He carried a bunch of bananas in his mouth, found a spot, and just sat down to eat, totally oblivious to all of us staring and photographing him.

And then over on the other side, we noticed a teenager who was a bright, bright orange and the younger orangutans tend to be. He was climbing down a tall tree heading for the food. And boy was he beautiful.

We stayed about two hours, just watching and watching them. This was my first sighting of an orangutan in the wild, or at least not in a zoo. We would see more later, some really in the wild, but, as they say, there is nothing like that first time. What a magnificent creature. The males indeed could be identified by their flanges. And that red fur! What a color. Beautiful.

Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre

Two days later, after we had headed to the Sepilok area of Borneo, we visited the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, just down the street from our hotel. Here too the orangutans are being rehabilitated.

At the entrance, we could make believe we were orangutans.

And Harsha, our fearless leader, took a turn posing as well.

And of course, we were not the only ones there. We ran into a group of students who all wanted their pictures taken with some of us. Linda, one of our travel mates, posed with them.

The center is made up of a series of wooden walkways that go through the jungle for 15 square miles. It is full of swingable vines, trees full of fruit and fresh shoots for snacking, and the branches of the Ironwood trees for building nests. But for us visitors, the focus was a raised platform feeding station where fruit is laid out to supplement the diet of those orangutans who haven’t quite yet learned how to forage for their food.

The orangutans had to fight for the fruit, however, as the local macaque monkeys have learned that there is a free buffet here twice a day.

We again watched for a while before making our way along the walkways to a building with large glass windows behind which we watched orphaned orangutans, mothers and babies and of course, lots more macaque monkeys.

Bornean Pygmy Squirrel

As we walked along the boardwalk, through the forest, Harsha suddenly called out, “Look, a pygmy squirrel!” We looked at the tree and there was something that looked like a mouse. The pygmy squirrel lives in the tall forests of Borneo and is mostly seen on the trunks of trees. It is called a bark gleaner as it eats the bark. It is a tiny, tiny, with olive brown fur on the back of its neck and on the top of its head, with a brown/orange tail. Weighing about half an ounce, it is the smallest diurnal squirrel in the world. And it is only found here in Sabah, Borneo! How lucky were we to see this rare animal?!

Orangutans in the Wild

On our 7th day of the trip, while on the Kinabatangan River, the longest river in the Sabah area, we got to see our first orangutan in the wild. As we floated down the river, we suddenly noticed her way up in the tree, just sitting there and reaching out here and there for fruit.

Palm oil

You can’t talk about orangutans and Borneo without mentioning palm oil. Palm oil is a very large industry in Borneo. While it provides employment and income for a large part of the population, it also has contributed to 35% loss of forest as new palm tree plantations are planted. It’s complicated…

How is palm oil used? It is used in everything from soap, detergent, lipstick and other cosmetics, pizza, ice cream, margarine, peanut butter, chips, vegan cheese, baby formula and even biodiesel, just to name a few. And Indonesia and Malaysia (which included Borneo) produce about 85% of the world’s palm oil.

As we were driving around, we saw palm oil plantation after plantation, with rows and rows of palm trees. The number of plantations was staggering.

And these plantations create jobs. But the jobs are hard and pay is low. As you can see in the pictures, one man collects the fruit of the palm and using a spike, swings it onto a cart pulled by a buffalo. Then, when it reaches the truck, another man, also using something like a pitchfork, swings the fruit onto the truck. Some communities are part owners and get some money back.

As we drove around to different areas, we would see piles of palm nuts on the ground, waiting to be picked up.

But these same plantations also create deforestation. A school, the children learn about the importance of wildlife and that tourism also creates jobs. As I said, it is complicated…

Why did palm oil plantations get started?

For most of its history, Borneo had no inhabitants. The climate is difficult and the forests are dense. In the last 50 years, this has changed with more than 500,000 people migrating in. This doubled the population, creating a need for jobs, which were nonexistent. The rubber and logging industries provided lots of employment until that market collapsed. As unemployment increased, the rise of palm oil plantations was seen as a welcome opportunity. But the environmental impact was huge.

In order to plant palm trees, the forests had to be destroyed. And then there is the less obvious environmental impact. Bio-diversity decreases; the orangutans and other animals can no longer move through the forests as they no longer exist. They lose their habitat. When they hang around the palm oil plantations, they are considered crop pests which puts them at risk from the managers of the plantations. Herbicides and pesticides polluted the waters.

So, for all these reasons and more, the Borneo government is now restricting the number of palm oil plantations. But even that is complicated…

More to come…

I don’t want to end this post on the down note. Borneo is a beautiful country full of wonderful people and wonderful wildlife. Every developing country has it growth pains. Please keep a look out for more posts about Kuching, about proboscis monkeys and frogs and insects and snakes and monkeys and sun bears and so much more.

Daniel Gurtner

I’ve heard before (probably from a video on YouTube) that orangutans don’t build mattresses/nests because they need them for sleeping on/in but rather “because they can.” Have you heard this before? Did anyone at the nature reserve or rehabilitation center say anything about that?

Rosana Ribeiro

Hello Sonia,

great to hear you are so busy travelling!

I am going to Malasya next week, but Borneo will be in a future trip.

Thanks for the rich information,

All the best,

Rosana – Nat Hab – São Paulo – Brazil